Ruta de navegación

Blogs

Entradas con Categorías Global Affairs Seguridad y defensa .

15 de junio, 2021

ENSAYO / Paula Mora Brito [Versión en inglés]

El terrorismo en el Sahel es una realidad ignorada que afecta a millones de personas. No es de extrañar que la región sea una de las más afligidas por esta práctica. Sus complejas características geográficas dificultan el control de las fronteras (especialmente las del desierto del Sáhara), y la falta de homogeneidad cultural y religiosa, junto a los continuos retos económicos y sociales, agravados por la pandemia del COVID-19, hacen de la región un escenario frágil y conveniente para los grupos terroristas. Además, los países occidentales (principalmente Francia) están presentes en la zona, provocando cierto rechazo en lo relativo a su intervención a los ojos de la población saheliana. Aunque los datos sobre esta problemática son escasos, lo que dificulta su estudio, este artículo tratará de ampliar los conceptos y conocimientos sobre el terrorismo en el Sahel, ampliando su espectro geográfico, para mostrar la vida cotidiana de sus habitantes desde hace varios años. Se pondrá el foco del análisis en la intervención occidental en la lucha contra el terrorismo.

El fenómeno terrorista

El terrorismo es un concepto controvertido, pues está sujeto a la interpretación individual: mientras unos condenan a un grupo por el uso de violencia indiscriminada bajo un objetivo político/social/económico, otros consideran a sus integrantes héroes de la libertad. Solamente su fin define esta actividad: coaccionar e intimidar la intención general sobre una cuestión. Se desarrolla bajo diferentes formas: por el ámbito geográfico (regional, nacional o internacional) o por su objetivo (etno-nacionalista, ideología política y/o económica, religioso o asuntos concretos). Es por ello que cada uno posee unas características distintas.

El terrorismo religioso, como resaltó Charles Townshend en su libro Terrorism: A very short introduction, posee unas características propias. Citando a Hoffman, explica que el objetivo transciende más allá de la política debido a que se considera una demanda teológica. Es una relación bilateral entre los fanáticos y Dios, en la que no cabe posibilidad de diálogo o entendimiento, solo el establecimiento de la demanda. Esta concepción conlleva a que sea un terrorismo internacional, aunque empiece a nivel regional o nacional, pues el grupo de “enemigos” es más amplio. El mesianismo es el motor de esta actividad, y el martirio su arma más potente. La muerte proveniente de la lucha, se presenta como un acto sagrado y refleja la certeza de los integrantes de estos grupos a su ideología.

Occidente tiene dificultades para abordar estas amenazas, pues entiende el mundo de manera secular. Sin embargo, los Estados en los que se desarrollan estos grupos, la religión representa la nación, los valores y el estilo de vida: el individuo es religión y viceversa. Como dijo Edward Said: “El arraigado Occidente, es ciego ante los matices y al cambio en el mundo islámico”. Y es que el terrorismo religioso islámico surge como una respuesta al colonialismo y a la práctica de soft power en las culturas árabes e islámicas, que se ha reforzado a través de la corriente del fundamentalismo islámico.

El terrorismo en el Sahel

El Sahel (“borde, costa” en árabe) es una ecorregión que hace de transición entre el norte y el sur del continente africano, así como de oeste a este, con un área total de 3.053.200 km², constituyendo un cinturón de 5.000 km. Está compuesto por Senegal, Mauritania, Malí, Argelia, Burkina-Faso, Níger, Nigeria, Chad, Sudán, Eritrea y Etiopía. Se trata de una zona privilegiada, pues el desierto se entiende como una vía de comunicación.

El área cuenta con 150 millones de habitantes, de los que el 64% son menores de 25 años y mayoritariamente islámicos suníes. En 2018, el último año que hay datos sobre estos países, la tasa de mortalidad anual por cada 1.000 personas era de 8,05, un índice muy alto comparado con el 2,59 de España en el 2019. La tasa de alfabetización de adultos (mayores de 15 años), de las que solo hay datos de siete de los diez países, es de un 56,06 %. En realidad, es muy desigual: mientras que Argelia posee un 81,40%, Níger o Malí tienen un 35%. La tasa sobre la incidencia de la pobreza sobre la base de la línea de pobreza nacional es de del 41,15% (solo cuatro países tienen datos del 2018). La esperanza de vida es de 63 años.

El territorio encara una crisis económica, política y social. El Sahel es una de las regiones más pobres del mundo, con el norte de Nigeria como uno de los territorios con la mayor cantidad de población extremadamente pobre del planeta. La situación empeoró este año con una caída histórica del precio de las materias primas (más del 20%), que representan un 89% de sus exportaciones. La crisis medioambiental dificulta el desarrollo económico.

El cambio climático ha provocado que el aumento de temperaturas vaya a un ritmo 1,5 veces más rápido que el de la media mundial, lo que ha multiplicado las sequías (de una cada diez años a una cada dos). La inestabilidad política de algunos países, como el Golpe de Estado del 2012 en Malí, dificultan su desarrollo económico.

En este contexto, la inseguridad se ha incrementado desde los ataques del 2004 en el Borno, estado de Nigeria que hace frontera con Camerún y Chad, por parte del grupo terrorista islámico Boko Haram. La actividad terrorista se ha extendido a través de la dirección de Al-Qaeda en el Magreb Islámico (AQIM), presentes en el norte de Malí, el este de Mauritania, Níger y el oeste de Chad. Esto ha propiciado una crisis demográfica, provocando que 4,2 millones de personas se hayan desplazado y más de un millón se vea incapaz de encontrar trabajo. El programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo estima que, de hoy a 2050, más de 85 millones de sahelianos se verán obligados a emigrar.

La mayoría de ataques tienen lugar en las triple frontera de Malí, Burkina-Faso y Níger; y la de Níger, Nigeria y Chad. Desde el Tratado de Berlín de 1885, las fronteras africanas han supuesto un grave problema ya que fueron una imposición europea que no respetó la realidad tribal y étnica de muchas regiones, obligando y creando una nación de la que sus habitantes no se sienten parte. Esta realidad se reflejó con el caso de Malí, mostrando la fragilidad preexistente de la región.

AQMI ha dividido en katibas (ramas) el Sahel: la Yahia Abou Ammar Abid Hammadu, que se establece entre el sur de Argelia y Túnez y el norte de Níger; y Tarik Ben Ziyad, activa en Mauritania, el sur de Argelia y el norte de Mali. La primera, es conocida por ser más “terrorista”, mientras que la segunda es más bien “criminal”. Esto se debe al mayor grado de crueldad empleado por la Hammadu, pues siguen el takfirismo (guerra contra los musulmanes “infieles”) de Zarqawi (ISIS).

Se apoderan de los territorios a través de negociaciones, en los que establecen un mercado de trafico ilegal. Una vez adquirida un área, establecen sus asentamientos, sus campamentos de entrenamiento y preparan sus próximos atentados. Otro medio de financiación es el secuestro. Es una forma de subyugar, humillar y conseguir ingresos de Occidente. La necesidad de dinero, a diferencia de una organización criminal, no es para el enriquecimiento personal de los componentes, sino para seguir financiando la actividad: comprar lealtades, armas, etc. Del reclutamiento no existen datos de su desarrollo, condiciones, ni objetivos por edades, clase ni sexo.

Las características geográficas y sociopolíticas de la ecorregión han obligado a AQMI ha desarrollar su capacidad de adaptación, como la subdivisión del grupo (Boko Haram), que muestra que ya no necesitan una base física fija como en los años 90s (AQ en Afghanistán). Además, se ha registrado un cambio de estrategia, pues estos grupos están aumentando en un 250%, sus ataques a organizaciones internacionales o infraestructuras del gobierno, y decreciendo los atentados a civiles. Esto puede ser una nueva forma de atraer a los locales pues se promocionan como protectores frente al abuso estatal.

En el 2019 hubo una media de 69,5 ataques mensuales en el Sahel y el Magreb, y el pasado mes de marzo se registraron 438 fallecidos. En 2020 ha disminuido la actividad debido al COVID-19. El terrorismo trae inseguridad política y social, así como económica, pues los inversores no se ven atraídos para hacer negocios en una zona inestable, provocando el mantenimiento de la precariedad. Esto provoca y/o mantiene el subdesarrollo de un estado, ocasionando un gran flujo de migración. Se entra entonces en el círculo vicioso del subdesarrollo y pobreza.

Para España, el suceso más reciente e impactante tuvo lugar el pasado 28 de abril de 2021, cuando los periodistas David Beriain y Roberto Fraile fueron asesinados en Burkina-Faso por la Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin, Grupo de Apoyo al Islam y a los Musulmanes en español; un grupo terrorista vinculado a Al-Qaeda.

La reciente y repentina muerte del presidente chadiano Idris Déby Itno, el 19 de abril de 2021, a manos de los Combatientes del Frente para el Cambio y la Concordia en el Chad (FACT por sus siglas en inglés Fighters of the Front for Change and Concord in Chad), ha aumentado aún más la inestabilidad en la región. El presidente de las últimas tres décadas luchaba contra este grupo rebelde, creado en 2016 en Libia, que pretendía arrojar a Déby y al régimen dinástico de Chad. Desde que se produjo este suceso, masivas protestas han cubierto las calles de Chad, pidiendo una transición democrática en el país, a lo que el ejército ha respondido matando a algunos de los manifestantes. Este levantamiento se debe a lo que a los chadianos les parece una repetición de su historia y la violación de la constitución de la nación. El ejército chadiano había anunciado la formación de un Consejo de Transición, que duraría 18 meses, bajo el liderazgo de Mahamat Idriss Déby, el hijo del anterior presidente. El problema es que su padre, en 1999, creó el mismo órgano político y prometió lo mismo. Sin embargo, sus promesas no se cumplieron. El Consejo Militar de Transición suspendió la Constitución, en la que se establece en su Título Decimoquinto que el presidente transnacional debe ser el presidente de la Asamblea Nacional.

La situación del Chad es clave en la lucha contra el terrorismo en el Sahel. El país se encuentra entre el Sahel y el Cuerno de África. La retirada o el debilitamiento de las tropas en las fronteras del país suponen un gran riesgo no sólo para Chad, sino también para sus vecinos. Los países fronterizos con el Chad, se verán expuestos a los violentos ataques de los grupos terroristas, ya que Chad cuenta con la mayor fuerza conjunta del G5 Sahel. El país es el estabilizador de la región. Al este, impide que la inestabilidad política sudanesa se extienda por las fronteras. Al sur, Chad ha sido el nuevo hogar de más de 500.000 refugiados que provienen de la República Centroafricana y su enorme crisis migratoria. Al oeste, contrarresta principalmente a Boko Haram, que ahora es un actor importante en Níger y Nigeria. Al norte, contrarresta a los grupos rebeldes libios. Es importante entender que, aunque Libia no forme parte del Sahel, su inestabilidad resuena con fuerza en la región, ya que el país es el nuevo centro de los grupos terroristas en el Sahel, como parece demostrar la muerte del expresidente. El país se ha convertido en la plataforma de lanzamiento de los grupos terroristas de África que pretenden imponer su voluntad en todo el continente. Queda por ver lo que ocurre en Chad, porque cambiará por completo el actual paradigma saheliano.

La lucha occidental contra el terrorismo

Existen iniciativas institucionales para abordar estas cuestiones regionales de forma conjunta, como el grupo G5 Sahel, compuesto por Mauritania, Mali, Níger, Burkina- Faso y Chad, contando con el apoyo de la Unión Africana, la Unión Europea, las Naciones Unidas o el Banco Mundial, entre otros.

También hay ayuda internacional a la región, principalmente de Francia y la Unión Europea. Desde 2013, a petición del gobierno de Malí, el gobierno francés puso en marcha la Operación "Serval" con el objetivo de expulsar a los grupos terroristas en el norte de Malí y otras naciones del Sahel. Le sucedió un año después la Operación "Barkhan", que se centra en la asistencia a los Estados miembros del G5 del Sahel, tratando de proporcionar los recursos y la formación necesarios para que estos países puedan gestionar su propia seguridad de forma independiente. En esta Operación también participan España, Alemania, Estonia y el Reino Unido. El año pasado, 2020, se puso en marcha la Task Force "Takuba", compuesta por fuerzas especiales francesas y estonias, en el cinturón Sáhara-Sahel. A día de hoy, Francia ha desplegado 5.100 militares, ha entrenado a más de 7.000 soldados del G5 Sahel, ha desplegado 750 actividades de entrenamiento o apoyo al combate y tiene 75 oficiales de cooperación en la región.

Francia también ha liderado la intervención internacional en el Sahel. En 2012, en el Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas promovió la Resolución 2085 para subrayar la necesidad de asistencia internacional en la región. En 2017, Francia fue la precursora de la Misión Multidimensional Integrada de Estabilización de las Naciones Unidas en Malí (MINUSMA), creada en virtud de la Resolución 2391 para prestar asistencia al gobierno de Malí en la estabilización de su país. Cuenta con más de 15.000 efectivos civiles y militares que prestan apoyo logístico y operacional.

La Unión Europea también ha participado a través de tres misiones principales en el marco de la Política Común de Seguridad y Defensa (PCSD): Misión de Formación de la Unión Europea (EUTM) Malí, EUCAP Sahel Malí y EUCAP Sahel Níger. La primera se creó en 2013 para formar y asesorar a las fuerzas armadas malienses. También coopera con los Estados miembros del G5 Sahel para mejorar el control de las fronteras. Las otras dos son misiones civiles cuyo objetivo es formar a la policía, la gendarmería y la guardia nacionales, así como asesorar las reformas de seguridad del gobierno nacional. La EUCAP Sahel Níger se creó en 2012 y sigue en vigor. En cuanto a la EUCAP Sahel Malí, se creó en 2014 y se ha prolongado hasta 2023. Además, Francia y la Unión Europea también contribuyen financieramente a la región. El año pasado, la Unión Europea aportó 189,4 millones de euros a la región. Francia aportó alrededor de 3.970 millones de euros durante 2019-2020.

Sin embargo, la incertidumbre por la muerte de Déby ha reconfigurado la percepción local de la intervención occidental, principalmente la francesa. Las protestas que han tenido lugar estas últimas semanas en el Chad también han supuesto una acusación a Francia por respaldar al consejo militar en contra de la voluntad del pueblo. Junto con la Unión Africana y la Unión Europea, Macron declaró en el funeral de Déby "Francia nunca podrá hacer que nadie cuestione (...) y amenace, ni hoy ni mañana, la estabilidad y la integridad de Chad", tras las promesas de Mahamat de "mantenerse fiel a la memoria" de su padre. Estas declaraciones fueron entendidas por los chadianos como que Mahamat seguirá el estilo de liderazgo de su padre y que a Francia no le importa la opresión que ha sufrido el pueblo durante décadas. Es en este punto donde Francia se arriesga a sólo preocuparse por la estabilidad que aportaba Chad en la región, sobre todo en sus intereses geopolíticos en lo que respecta especialmente a Libia y África Occidental. Quizás por ello Macron sintió la necesidad de aclarar una semana después sus palabras: "Seré muy claro: apoyé la estabilidad y la integridad de Chad cuando estuve en N'Djamena. Estoy a favor de una transición pacífica, democrática e inclusiva, no estoy a favor de una sucesión", dijo. No obstante, los sahelianos se están cansando de ser las marionetas de los juegos occidentales, como se ha demostrado este año en Malí con las protestas de los habitantes contra la presencia militar francesa en el país. Occidente debe mostrar su compromiso real con el fomento de los derechos humanos presionando por una transición democrática mientras mantiene su lucha contra el terrorismo.

En conclusión, el terrorismo religioso islamista ha ido en aumento en los últimos años como contrapunto al poder de Estados Unidos en la Guerra Fría. El Sahel es uno de los escenarios predominantes de estas actividades, ya que es una zona con inestabilidad político-económica preexistente que los terroristas han aprovechado. El terrorismo está cambiando sus formas de actuar, mostrando su adaptabilidad en términos de geografía, métodos de actuación y adquisición de recursos. Francia ha demostrado ser el líder de la iniciativa occidental en la región y ha hecho progresos en la misma. Sin embargo, Occidente, especialmente los países europeos, deben empezar a prestar más atención a las causas de los problemas de esta región, recopilando datos y conociendo su realidad. Sólo entonces podrán abordar estos problemas con eficacia, ayudando a las instituciones regionales existentes, buscando soluciones a largo plazo que satisfagan a la población.

COMMENTARY / Jairo Císcar

Since the end of the Second World War, collective security on the European continent and with it, peace, has been a priority. The founding fathers of the European Union themselves, aware of the tensions that resulted from the First and Second World Wars, devised and created security structures to prevent future conflicts and strengthen relations between former enemies. The first structure, although not purely military, obeys this logic: the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), essential for the creation and maintenance of industry and armies, was created by the Treaty of Paris in 1951, introducing a concept as widely used today as “energy security”. This was arguably the first major step towards effective integration of European countries.

However, for the issue at hand, the path has been much more complicated. In the same period in which the ECSC was born, French Prime Minister René Pleven, with the encouragement of Robert Schuman and Jean Monet, wanted to promote the European Defence Community. This ambitious plan aimed to merge the armed forces of the six founding countries (including the Federal Republic of Germany) into a European Armed Forces that would keep the continent together and prevent the possibility of a new conflict between states. Ambitious as it was, the project failed in 1954, when the deeply nationalist Gaullist deputies of the French National Assembly refused to ratify the agreement. European integration at the military level thus suffered a setback from which it would not begin to recover until the present century, although it continues to face many of the reluctances it once did.

Why did the European Defence Community fail, and what makes the European Armed Forces still a difficult debate today? This is a question that needs to be analysed and understood, for while political and economic integration has advanced with a large consensus, the military problem, which should go hand in hand with the two previous issues, has always been the Achilles' tendon of the common European project.

There are basically two factors to take into account. The first is the existence of a larger defence community, NATO. Since 1948, NATO has been the principal military alliance of Western countries. Born to counter Soviet expansionism, the Alliance has evolved in size and objectives to its current configuration of 30 member states and a multitude of other states in the form of strategic alliances. Although NATO's primary purpose was diluted after the fall of the Berlin Wall, it has evolved with the times, remaining alert and operational all around the globe. The existence of this common, powerful and ambitious project under U.S. leadership largely obscured efforts and intentions to create a common European defence project. Why create one, overlapping, structure if the objectives were practically the same and NATO guaranteed greater logistical, military superiority and a nuclear arsenal? For decades, this has been the major argument against further European integration in the field of defence - as protection was secured but delegated.

Another issue was the nationalism still prevalent among European states, especially in the aforementioned Gaullist France. Even today, with an ongoing and deep political, economic and, at a certain level, judicial integration, military affairs are still often seen as the last bastion of national sovereignty. In Schengen Europe, they remain for many the guarantee of those borders that fell long ago.

Other issues to take into account are the progressive detachment of the population from the armed forces (a Europe that has not seen war on its own territory in 70 years, except for the Balkans, has tended to settle into peace, nearly oblivious to wars) and its progressive ageing, with a future with fewer people of military age, and who, as we have mentioned, often have an ideological and motivational gap with previous generations with respect to the concept and utility of the military.

It was not until relatively recently, with the Treaty of Amsterdam in 1999, that the embryonic mechanisms of the current Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), supervised by the European Defence Agency, began to be implemented. In the 2010s, with the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, these mechanisms were established. The Military Staff of the European Union (EUMS) is one of them. It constitutes the EU's first permanent strategic headquarters. The final impetus came in 2015, with the European Union Global Strategy. This led to the creation of various far-reaching initiatives, most notably the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), which since 2017 has been pursuing the structural integration of the Armed Forces of all EU countries except Denmark and Malta. It is not only limited to proper integration, but also leads capability development projects such as the EU Collaborative Warfare Capabilities (ECOWAR) or the Airborne Electronic Attack (AEA), as well as defence industry endeavors such as the MUSAS project, or the CYBER-C4ISR capabilities level.

Although it is too early to say for sure, Europe may be as close as it can get to René Pleven's distant dream. The EU's geopolitical situation is changing, and so is its own language and motivation. If we used to talk about Europe delegating its protection for years, now Emmanuel Macron advocates ‘strategic autonomy” for the EU. It should be recalled that just over a year ago he claimed that “NATO is brain-dead”. Some voices in the EU’s political arena claim and have realised that it can no longer delegate the European protection and defence of its interests, and they are starting to take steps towards doing so. Despite these advances, it is true that is not a shared interest, at least, as a whole. France and other Mediterranean member states are pushing towards it, but those in the East, as Poland or Latvia, are far more concerned about the rise of Russia, and are comfortable enough for U.S. troops to be established in their terrain.

Having said that, I truly believe that the advantages of the European Armed Forces project outweigh its negative aspects. First of all, a Europe united in defence policies would not imply the disappearance of NATO, or the breaking of agreements with third countries. In fact, these alliances could even be strengthened and fully adapted to the 21st century and to the war of the future. As an example, in 2018 the EU and NATO signed collaboration agreements on issues such as cybersecurity, defence industry and military mobility.

While NATO works, Europe is now facing a dissociation between U.S. interests and those of the other Allies, especially the European ones. In particular, countries such as France, Spain and Italy are shifting their defence policies from the Middle East, or the current peace process in Afghanistan (which, despite 20 years of war, sounds like a long way off), to sub-Saharan Africa (Operation “Barkhane” or EUTM Mali), a much closer region with a greater impact on the lives of the European citizens. This does not detract from the fact that NATO faces global terrorism in a new era that is set to surpass asymmetric warfare and other 4th generation wars: the era of hybrid warfare. Russia's military build-up on the EU's eastern flank and China's penetration into Africa do not invite a loosening of ties with the United States, but European countries need to prioritise their own threats over those of the U.S., although it is true that the needs of countries to the west of the EU are not the same as those to the east. This could be the main stumbling block for a joint European Army, as weighting the different strategic priorities could be really arduous.

It is true that this idea of differing policies is not shared in the EU as a whole. Countries such as Poland, those in the Balkans or the Baltic have different approaches and necessities when talking about a European Union common security strategy. The EU is a 27 country-wide body that often is extremely difficult to navigate within. Consensus is only reached after very long discussions (see the soap opera on the COVID relief package negotiations), and being defence as important as it is, and in need of fast, executive decision making, the intricate bureaucracy of the EU could not help with it. But if well managed, it could be an opportunity to develop new strategies for decision-making and reforming the European system as a whole, fostering a new, more effective Europe.

Another debate, probably outdated, is the one who claims that the EU is not capable of planning, organising and conducting operations outside the NATO umbrella. In this case, apart from the aforementioned guidelines and policies, one simply has to look at the facts: the EU today leads six active (and 18 completed) military missions with close to 5,000 troops deployed. The “Althea” (Bosnia & Herzegovina) and “Atalanta” (in the Indian Ocean) missions are particularly noteworthy. It is true that these examples are of low-intensity conflicts but, given the combat experience of EU nations under NATO or in other missions (French and Portuguese in Africa, etc.) combat-pace could be quickly achieved. The NATO certification system under which most European armed forces operate guarantees standardisation in tactics, logistics and procedures, so that standardisation at the European level would be extremely simple if existing models are taken into account.

Another issue is the question of whether the EU could politically and economically engage in a long, high-intensity operation without getting drowned by the public opinion, financial administration, and, obviously, with the planning and carrying out of a whole campaign. This is one of the other main problems with future European armed forces because, as mentioned earlier, Europeans are not prepared in any way to be confronted with the reality of a situation of war. What rules of engagement will be used? How to cope with casualties? And even more, how to create an effective chain of command and control among 27 countries? And what will happen if one does not agree with a particular intervention or action? How could it be argued that the EU, world’s leading beacon of human rights, democracy and peace, gets engaged in a war? Undoubtedly, these questions have rational and objective answers, but in an era of social media, populism, empty discourses, and fake news, it would be difficult to engage with the public (and voters) to support the idea.

Having said that, there is room for optimism. Another reason pointing towards Europe's armed forces is the collaboration that exists at the military industrial level. PESCO and the European Defence Fund encourage this, and projects such as the FCAS and EURODRONE lay the foundations for the future of European armed forces capabilities. It should not be forgotten that the European defence industry is the world leader behind that of the United States and is an increasingly tough competitor for the latter.

In addition, the use of military forces in European countries during the current coronavirus pandemic has served to reinforce the message of their utility and need for collaboration beyond the purely military. While the militarisation of emergencies must be avoided and the soldier must not be reduced to a mere “Swiss army knife” at disposition of the government trying to make up their own lack of planning or capacity to deal with the situation, it has brought the military closer to the streets, and to some extent may have helped to counteract the disaffection with the armed forces that exists in many European countries (due to the factors mentioned above).

Finally, I believe that European-level integration of the armed forces will not be merely beneficial, but necessary for Europe. If the EU wants to maintain its diplomacy, its economic power, it needs its own strategic project, an “area of control” over its interests and, above all, military independence. This does not preclude maintaining and promoting the alliances already created, but this is a unique and necessary opportunity to fully establish the common European project. The political and economic framework cannot be completed without the military one; and the military one cannot function without the former. All that remains is to look at the direction the EU is taking and hope that it will be realised. It is more than possible and doable, and the reality is that work is being done towards it.

COMMENTARY / Marina G. Reina

After weeks of rockets being fired from Gaza and the West Bank to Israel and Israeli air strikes, Israel and Hamas have agreed to a ceasefire in a no less heated environment. The conflict of the last days between Israel and Palestine has spread like powder in a spiral of violence whose origin and direct reasons are difficult to draw. As a result, hundreds have been killed or injured in both sides.

What at first sight seemed like a Palestinian protest against the eviction of Palestinian families in the Jerusalem’s neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah, is connected to the pro-Hamas demonstrations held days before at Damascus Gate in Jerusalem. And even before that, at the beginning of Ramadan, Lehava, a Jewish far-right extremist organization, carried out inflammatory anti-Arab protests at the same Damascus Gate. Additionally, the upcoming Palestinian legislative elections that Palestinian PM Mahmoud Abbas indefinitely postponed must be added to this cocktail of factors. To add fuel to the flames, social media have played a significant role in catapulting the conflict to the international arena—especially due to the attack in Al-Aqsa mosque that shocked Muslims worldwide—, and Hamas’ campaign encouraging Palestinian youth to throw into the streets at point of rocks and makeshift bombs.

Sheikh Jarrah was just the last straw

At this point in the story, it has become clear that the evictions in Sheikh Jarrah have been just another drop of water in a glass that has been overflowing for decades. The Palestinian side attributes this to an Israeli state strategy to expand Jewish control over East Jerusalem and includes claims of ethnic cleansing. However, the issue is actually a private matter between Jews who have property documents over those lands dating the 1800s, substantiated in a 1970 law that enables Jews to reclaim Jewish-owned property in East Jerusalem from before 1948, and a group of Palestinians, not favored by that same law.

The sentence ruled in favor of the right-wing Jewish Israeli association that was claiming the property. This is not new, as such nationalist Jews have been working for years to expand Jewish presence in East Jerusalem’s Palestinian neighborhoods. Far from being individuals acting for purely private purposes, they are radical Zionist Jews who see their ambitions protected by the law. This is clearly portrayed by the presence of the leader of the Jewish supremacist Lehava group—also defined as opposed to the Christian presence in Israel—during the evictions in Sheikh Jarrah. This same group marched through Jerusalem’s downtown to the cry of “Death to Arabs” and looking for attacking Palestinians. The fact is that Israel does not condemn or repress the movements of the extreme Jewish right as it does the Islamic extremist movements. Sheikh Jarrah is one, among other examples, of how, rather, he gives them legal space.

Clashes in the streets of Israel between Jews and Palestinians

Real pitched battles were fought in the streets of different cities of Israel between Jewish and Palestinians youth. This is the case in places such as Jerusalem, Acre, Lod and Ashkelon —where the sky was filled with the missiles coming from Gaza, that were blocked by the Israeli antimissile “Iron Dome” system. Palestinian neighbors were harassed and even killed, synagogues were attacked, and endless fights between Palestinians and Israeli Jews happened in every moment on the streets, blinded by ethnic and religious hatred. This is shifting dramatically the narrative of the conflict, as it is taking place in two planes: one militarized, starring Hamas and the Israeli military; and the other one held in the streets by the youth of both factions. Nonetheless, it cannot be omitted the fact that all Israeli Jews receive military training and are conscripted from the age of 18, a reality that sets the distance in such street fights between Palestinians and Israelis.

Tiktok, Instagram and Telegram groups have served as political loudspeakers of the conflict, bombarding images and videos and minute-by-minute updates of the situation. On many occasions accused of being fake news, the truth is that they have achieved an unprecedented mobilization, both within Israel and Palestine, and throughout the world. So much so that pro-Palestinian demonstrations have already been held and will continue in the coming days in different European and US cities. Here, then, there is another factor, which, while informative and necessary, also stokes the flames of fire by promoting even more hatred. Something that has also been denounced in social networks is the removal by the service of review of the videos in favor of the Palestinian cause which, far from serving anything, increases the majority argument that they want to silence the voice of the Palestinians and hide what is happening.

Hamas propaganda, with videos circulating on social media about the launch of the missiles and the bloodthirsty speeches of its leader, added to the Friday’s sermons in mosques encouraging young Muslims to fight, and to sacrifice their lives as martyrs protecting the land stolen from them, do nothing but promote hatred and radicalization. In fact,

It may be rash to say that this is a lost war for the Palestinians, but the facts suggest that it is. The only militarized Palestinian faction is Hamas, the only possible opposition to Israel, and Israel has already hinted to Qatari and Egyptian mediators that it will not stop military deployment and attacks until the military wing of Hamas surrenders its weapons. The US President denied the idea of Israel being overreacting.

Hamas’ political upside in violence and Israel’s catastrophic counter-offensive

Experts declare that it seems like Hamas was seeking to overload or saturate Israel’s interception system, which can only stand a certain number of attacks at once. Indeed, the group has significantly increased the rate of fire, meaning that it has not only replenished its arsenal in spite of the blockade imposed by Israel, but that it has also improved its capabilities. Iran has played a major role in this, supplying technology in order to boost Palestinian self-production of weapons, extend the range of rockets and improve their accuracy. A reality that has been recognized by both Hamas and Iran, as Hamas attributes to the Persian country its success.

This translates into the bloodshed of unarmed civilians to be continued. If we start from the basis that Israeli action is defensive, it must also be said that air strikes do not discriminate against targets. Although the IDF has declared that the targets are bases of Hamas, it has been documented how buildings of civilians have been destroyed in Gaza, as already counted by 243 the numbers of dead and those of injured are more than 1,700 then the ceasefire entered into effect. On the Israeli side, the wounded reported were 200 and the dead were counted as 12. In an attempt to wipe out senior Hamas officials, the Israeli army was taking over residential buildings, shops and the lives of Palestinian civilians. In the last movement, Israel was focusing on destroying Hamas’ tunnels and entering Gaza with a large military deployment of tanks and military to do so.

Blood has been shed from whatever ethnical and religious background, because Hamas has seen a political upside in violence, and because Israel has failed to punish extremist Jewish movements as it does with Islamist terrorism and uses disproportionated defensive action against any Palestinian uprising. A sea of factors that converge in hatred and violence because both sides obstinately and collectively refuse to recognize and legitimate the existence of the other.

A brief outline of the European defense system, integrated into the European External Action Service and its importance to the Union

The European Union will launch the Conference on the Future of Europe on May 9th, marking the beginning of the event that will feature debates between institutions, politicians and civil society on several topics that concern the community, including security and defense. It is clear that the majority of the European Union favors a common defense effort, and the Union has taken steps to ensure a solid structure to lay the framework for a possible integration of forces. Following the efforts to unify foreign policy objectives, a unified defense is the next logical step for European integration.

Course for the Somali National Armed Forces, led by a Spanish Colonel with instructors from Italy, Sweden, Finland and Spain [EUTM-Somalia]

ARTICLE / José Antonio Latorre

According to the last standard Eurobarometer, around 77% of Europeans support a common defense and security policy among European Union member states. The support for this cause is irregular, with the backing spanning from 58% (Sweden) to 93% (Luxembourg). Therefore, it is expected that security and defense will definitely take a prominent role in the future of the Union.

In 2017, the European Commission launched the “White Paper on the Future of Europe,” a document that outlines the challenges and consequently the possible scenarios on how the Union could evolve by 2025. In the field of security, the document considers three different scenarios: Security and Defense Cooperation, Shared Security and Defense, and Common Defense and Security. In the first scenario, the member states would cooperate on a voluntary basis, similarly to an ad-hoc system. The second scenario details one where the tendency would be to project a stronger security, sharing military and economic capabilities to enhance efficiency. The final scenario would be one where members expand mutual assistance and take part in the integration of defense forces; this includes a united defense spending and distribution of military assets to reduce costs and boost capabilities.

Although these are three different predictions, what is clear is that the enhancement of European security is of greatest importance. As former European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said in the 2016 State of the Union address: “Europe can no longer afford to piggyback on the military might of others. We have to take responsibility for protecting our interests and the European way of life. It is only by working together that Europe will be able to defend itself at home and abroad.” He was referring to the paramountcy of a strategic autonomy that will permit the union to become stronger and have more weight in international relations, while depending less on the United States.

The existing framework on security

The European Union does not have to start from scratch to achieve these goals, since it currently has a Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC) branch. The bureau is situated within the EU Military Staff, part of the European External Action Service in Brussels. This operational headquarters was established on June 8th, 2017, with the aim of boosting defense capabilities for the European Union outside its borders. It was created in order to strengthen civil/military cooperation through the Joint Support Coordination Cell and the Civil Planning and Conduct Capability, avoiding unnecessary overlap with NATO. Its main responsibilities include operational planning and conduct of the current non-executive missions; namely the European Union Training Missions (EUTM) in Mali, Somalia and Central African Republic.

A non-executive mission is an operation conducted to support a host nation with an advisory role only. For example, EUTM Somalia was established in 2010 to strengthen the Somali federal defense institutions through its three-pillar approach: training, mentoring and advising. The mission is supporting the development of the Somali Army General Staff and the Ministry of Defense through advice and tactical training. The mission has no combat mandate, but it works closely with the EU Naval Force – Operation ATALANTA (prevention and deterrence of privacy and protection of shipping), EUCAP Somalia (regional civilian mission), and AMISOM (African Union peacekeeping mission in Somalia), in close cooperation with the European Union. The mission, which is located in Mogadishu, has a strength of over 200 personnel, with seven troop contributing states, primarily from Italy and Spain. Non-executive missions have a clear mandate of advising, but they can be considered as a prototype of European defense cooperation for the future.

The Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) is the framework for cooperation between EU member states in order to conduct missions to maintain security and establish ties with third countries through the use of military and civilian assets. It was launched in 1999 and it has become a bedrock for EU foreign policy. It gives the Union the possibility to intervene outside its borders and cooperate with other organizations, such as NATO and the African Union, in peacekeeping and conflict prevention. The CSDP is the umbrella for many branches that are involved with security and defense, but there is still a need for an enhancement and concentration of forces that will expand its potential.

Steppingstones for a larger, unified project

Like all the European Union, the CSDP is still a project that needs construction, and a European Union military should be a priority. In recent years, there have been efforts to implement measures to advance towards this goal. Firstly, Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) was launched in 2017 to reinforce defense capabilities and increase military coordination at an interoperable level. Participation is voluntary, but once decided, the country must abide by legally binding commitments. So far, 25 member states have joined the integrated structure, which depends on the European External Action Service, EU Military Staff and the European Defense Agency. Presently, there are 46 projects being developed, including a Joint EU Intelligence School, the upgrade of Maritime Surveillance, a European Medical Command and a Cyber and Information Domain Coordination Center, among the many others. Although critics have suggested that the structure will overlap with NATO competences, Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said that he believed “that PESCO can strengthen European defense, which is good for Europe but also good for NATO.” It is important to add that its alliance with NATO was strengthened through common participation in the cybersecurity sector, joint exercises, and counterterrorism. Secondly, the launch of the European Defense Fund in 2017 permits co-funded defense cooperation, and it will be part of the 2021-2027 long-term EU budget. Finally, the mentioned Military Planning and Conduct Capability branch was established in 2017 to improve crisis management and operational surveillance.

Therefore, it is a clear intention of the majority of the European Union to increase capabilities and unify efforts to have a common defense. Another aspect is that a common military will make spending more efficient, which will permit the Union to compete against powers like China or the United States. Again, the United States is mentioned because although it is an essential ally, Europeans cannot continue to depend on their transatlantic partner for security and defense.

A European Union military?

With a common army, the European Union will be a significant player in the international field. The integration of forces, technology and equipment reduces spending and boosts efficiency, which would be a historical achievement for the Union. European integration is a project based on peace, democracy, human dignity, equality, freedom and the protection and promotion of human rights. If the Union wants to continue to be the bearer of these values and protect those that are most vulnerable against the injustices of this century, then efforts must be concentrated to reach this objective.

The Union is facing tough challenges, from nationalisms and internal divides to economic and sanitary obstacles. However, it is not the first time that unity has been put at risk. Brexit has shown that the European project is not invulnerable, that it is still not fully constructed. The European way of life is a model for freedom and security, but this must be fought for and protected; it can never be taken for granted.

Europe has lived an unprecedented period of peace and prosperity due to past endeavors at its foundation. It is evident that there will always be challenges and critics, but the only way to continue to be a leader is through unification; and it starts with a European Army. There are already mechanisms in place to ensure cooperation, such as those explored with non-executive missions. These are the stepping-stones for defense coordination and partnerships in the future. Although it is a complex task, it seems more necessary than ever before. For the protection of Western values and culture, for the promotion of human rights and dignity, and for the defense of freedom and democracy, European integration at the defense level is the next step in the future of the European Union.

An update on the Iranian nuclear accord between 2018 and the resumed talks in April 2021

The signatories of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), reached in 2015 to limit Iran's nuclear program, met again on April 6 in Vienna to explore the possibility of reviving the accord. The US withdrawal after Donald Trump becoming president put the agreement on hold and lead Tehran to miss its commitments. Here we offer an update on the issue until the international talks resumed.

Trump's announcement of the US withdrawal from the JCPOA on May 8, 2018 [White House]

ARTICLE / Ana Salas Cuevas

The Islamic Republic of Iran is a key player in the stability of its regional environment, which means that it is a central country worth international attention. It is a regional power not only because of its strategic location, but also because of its large hydrocarbon reserves, which make Iran the fourth country in oil reserves and the second one in gas reserves.

In 2003, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) brought to the light and warned the international community about the existence of nuclear facilities, and of a covert program in Iran which could serve a military purpose. This prompted the United Nations and the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (the P5: France, China, Russia, the United States and the United Kingdom) to take measures against Iran in 2006. Multilateral and unilateral economic sanctions (the UN and the US) were implemented, which deteriorated Iran’s economy, but which did not stop its nuclear proliferation program. There were also sanctions linked to the development of ballistic missiles and to the support of terrorist groups. These sanctions, added to the ones the United States imposed on Tehran in the wake of the 1979 revolution, and together with the instability that cripples the country, caused a deep deterioration of Iran’s economy.

In November 2013, the P5 plus Germany (P5+1) and Iran came to terms with an initial agreement on Iran's nuclear program (a Joint Plan of Action) which, after several negotiations, translated in a final pact, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed in 2015. The European Union adhered to the JCPOA.

The focus of Iran's motives for succumbing and accepting restrictions on its nuclear program lies in the Iranian regime’s concern that the deteriorating living conditions of the Iranian population due to the economic sanctions could result in growing social unrest.

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action

The goal of these negotiations was to reach a long-term comprehensive solution agreed by both parties to ensure that Iran´s nuclear program would be completely peaceful. Iran reiterated that it would not seek or develop any nuclear weapons under any circumstances. The real aim of the nuclear deal, though, was to extend the time needed for Iran to produce enough fissile material for bombs from three months to one year. To this end, a number of restrictions were reached.

This comprehensive solution involved a mutually defined enrichment plan with practical restrictions and transparent measures to ensure the peaceful nature of the program. In addition, the resolution incorporated a step-by-step process of reciprocity that included the lifting of all UN Security Council, multilateral and national sanctions related to Iran´s nuclear program. In total, these obligations were key to freeze Iran’s nuclear program and reduced the factors most sensitive to proliferation. In return, Iran received limited sanctions relief.

More specifically, the key points in the JCPOA were the following: Firstly, for 15 years, Iran would limit its uranium enrichment to 3.67%, eliminate 98% of its enriched uranium stocks in order to reduce them to 300 kg, and restrict its uranium enrichment activities to its facilities at Natanz. Secondly, for 10 years, it would not be able to operate more than 5,060 old and inefficient IR-1 centrifuges to enrich uranium. Finally, inspectors from the IAEA would be responsible for the next 15 years for ensuring that Iran complied with the terms of the agreement and did not develop a covert nuclear program.

In exchange, the sanctions imposed by the United States, the European Union and the United Nations on its nuclear program would be lifted, although this would not apply to other types of sanctions. Thus, as far as the EU is concerned, restrictive measures against individuals and entities responsible for human rights violations, and the embargo on arms and ballistic missiles to Iran would be maintained. In turn, the United States undertook to lift the secondary sanctions, so that the primary sanctions, which have been in place since the Iranian revolution, remained unchanged.

To oversee the implementation of the agreement, a joint committee composed of Iran and the other signatories to the JCPOA would be established to meet every three months in Vienna, Geneva or New York.

United States withdrawal

In 2018, President Trump withdrew the US from the 2015 Iran deal and moved to resume the sanctions lifted after the agreement was signed. The withdrawal was accompanied by measures that could pit the parties against each other in terms of sanctions, encourage further proliferation measures by Iran and undermine regional stability. The US exit from the agreement put the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action on hold.

The United States argued that the agreement allowed Iran to approach the nuclear threshold in a short period of time. With the withdrawal, however, the US risked bringing this point closer in time by not waiting to see what could happen after the 10 and 15 years, assuming that the pact would not last after that time. This may make Iran's proliferation a closer possibility.

Shortly after Trump announced the first anniversary of its withdrawal from the nuclear deal and the assassination of powerful military commander Qasem Soleimani by US drones, Iran announced a new nuclear enrichment program as a signal to nationalists, designed to demonstrate the power of the mullah regime. This leaves the entire international community to question whether diplomatic efforts are seen in Tehran as a sign of weakness, which could be met with aggression.

On the one hand, some opinions consider that, by remaining within the JCPOA, renouncing proliferation options and respecting its commitments, Iran gains credibility as an international actor while the US loses it, since the agreements on proliferation that are negotiated have no guarantee of being ratified by the US Congress, making their implementation dependent on presidential discretion.

On the other hand, the nuclear agreement adopted in 2015 raised relevant issues from the perspective of international law. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action timeline is 10 to 15 years. This would terminate restrictions on Iranian activities and most of the verification and control provisions would expire. Iran would then be able to expand its nuclear facilities and would find it easier to develop nuclear weapons activities again. In addition, the legal nature of the Plan and the binding or non-binding nature of the commitments made under it have been the subject of intense debate and analysis in the United States. The JCPOA does not constitute an international treaty. So, if the JCPOA was considered to be a non-binding agreement, from the perspective of international law there would be no obstacle for the US administration to withdraw from it and reinstate the sanctions previously adopted by the United States.

The JCPOA after 2018

As mentioned, the agreement has been held in abeyance since 2018 because the IAEA inspectors in Vienna will no longer have access to Iranian facilities.

Nowadays, one of the factors that have raised questions about Iran’s nuclear documents is the IAEA’s growing attention to Tehran’s nuclear contempt. In March 2020, the IAEA “identified a number of questions related to possible undeclared nuclear material and nuclear-related activities at three locations in Iran”. The agency’s Director General Rafael Grossi stated: “The fact that we found traces (of uranium) is very important. That means there is the possibility of nuclear activities and material that are not under international supervision and about which we know not the origin or the intent”.

The IAEA also revealed that the Iranian regime was violating all the restrictions of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. The Iranian leader argued that the US first violated the terms of the JCPOA when it unilaterally withdrew the terms of the JCPOA in 2018 to prove its reason for violating the nuclear agreement.

In the face of the economic crisis, the country has been hit again by the recent sanctions imposed by the United States. Tehran ignores the international community and tries to get through the signatory countries of the agreement, especially the United States, claiming that if they return to compliance with their obligations, Iran will also quickly return to compliance with the treaty. This approach has put strong pressure on the new US government from the beginning. Joe Biden's advisors suggested that the agreement could be considered again. But if Washington is faced with Tehran's full violation of the treaty, it will be difficult to defend such a return to the JCPOA.

In order to maintain world security, the international community must not succumb to Iran’s warnings. Tehran has long issued empty threats to force the world to accept its demands. For example, in January 2020, when the UK, France and Germany triggered the JCPOA’s dispute settlement mechanism, the Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a direct warning, saying: “If Europeans, instead of keeping to their commitments and making Iran benefit from the lifting of sanctions, misuse the dispute resolution mechanism, they’ll need to be prepared for the consequences that they have been informed about earlier”.

Conclusions

The purpose of the agreement is to prevent Iran from becoming a nuclear power that would exert pressure on neighboring countries and further destabilize the region. For example, Tehran's military influence is already keeping the war going in Syria and hampering international peace efforts. A nuclear Iran is a frightening sight in the West.

The rising in tensions between Iran and the United States since the latter unilaterally abandoned the JCPOA has increased the deep mistrust already separating both countries. Under such conditions, a return to the JCPOA as it was before 2018 seems hardly imaginable. A renovated agreement, however, is baldly needed to limit the possibilities of proliferation in an already too instable region. Will that be possible?

IDF soldiers during a study tour as part of Sunday culture, at the Ramon Crater Visitor Center [IDF]

ESSAY / Jairo Císcar

The geopolitical reality that exists in the Middle East and the Eastern Mediterranean is incredibly complex, and within it the Arab-Israeli conflict stands out. If we pay attention to History, we can see that it is by no means a new conflict (outside its form): it can be traced back to more than 3,100 years ago. It is a land that has been permanently disputed; despite being the vast majority of it desert and very hostile to humans, it has been coveted and settled by multiple peoples and civilizations. The disputed territory, which stretches across what today is Israel, Palestine, and parts of Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, and Syria practically coincides with historic Canaan, the Promised Land of the Jewish people. Since those days, the control and prevalence of human groups over the territory was linked to military superiority, as the conflict was always latent. The presence of military, violence and conflict has been a constant aspect of societies established in the area; and, with geography and history, is fundamental to understand the current conflict and the functioning of the Israeli society.

As we have said, a priori it does not have great reasons for a fierce fight for the territory, but the reality is different: the disputed area is one of the key places in the geostrategy of the western and eastern world. This thin strip, between the Tigris and Euphrates (the Fertile Crescent, considered the cradle of the first civilizations) and the mouth of the Nile, although it does not enjoy great water or natural resources, is an area of high strategic value: it acts as a bridge between Africa, Asia and the Mediterranean (with Europe by sea). It is also a sacred place for the three great monotheistic religions of the world, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, the “Peoples of the Book”, who group under their creeds more than half of the world's inhabitants. Thus, for millennia, the land of Israel has been abuzz with cultural and religious exchanges ... and of course, struggles for its control.

According to the Bible, the main para-historical account of these events, the first Israelites began to arrive in the Canaanite lands around 2000 BC, after God promised Abraham that land “... To your descendants ...”[1] The massive arrival of Israelites would occur around 1400 BC, where they started a series of campaigns and expelled or assimilated the various Canaanite peoples such as the Philistines (of which the Palestinians claim to be descendants), until the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah finally united around the year 1000 BC under a monarchy that would come to dominate the region until their separation in 924 BC.

It is at this time that we can begin to speak of a people of Israel, who will inhabit this land uninterruptedly, under the rule of other great empires such as the Assyrian, the Babylonian, and the Macedonian, to finally end their existence under the Roman Empire. It is in 63 BC when Pompey conquered Jerusalem and occupied Judea, ending the freedom of the people of Israel. It will be in 70 AD, though, with the emperor Titus, when after a new Hebrew uprising the Second Temple of Jerusalem was razed, and the Diaspora of the Hebrew people began; that is, their emigration to other places across the East and West, living in small communities in which, suffering constant persecutions, they continued with their minds set on a future return to their “Promised Land”. The population vacuum left by the Diaspora was then filled again by peoples present in the area, as well as by Arabs.

The current state of Israel

This review of the historical antiquity of the conflict is necessary because this is one with some very special characteristics: practically no other conflict is justified before such extremes by both parties with “sentimental” or dubious “legal” reasons.

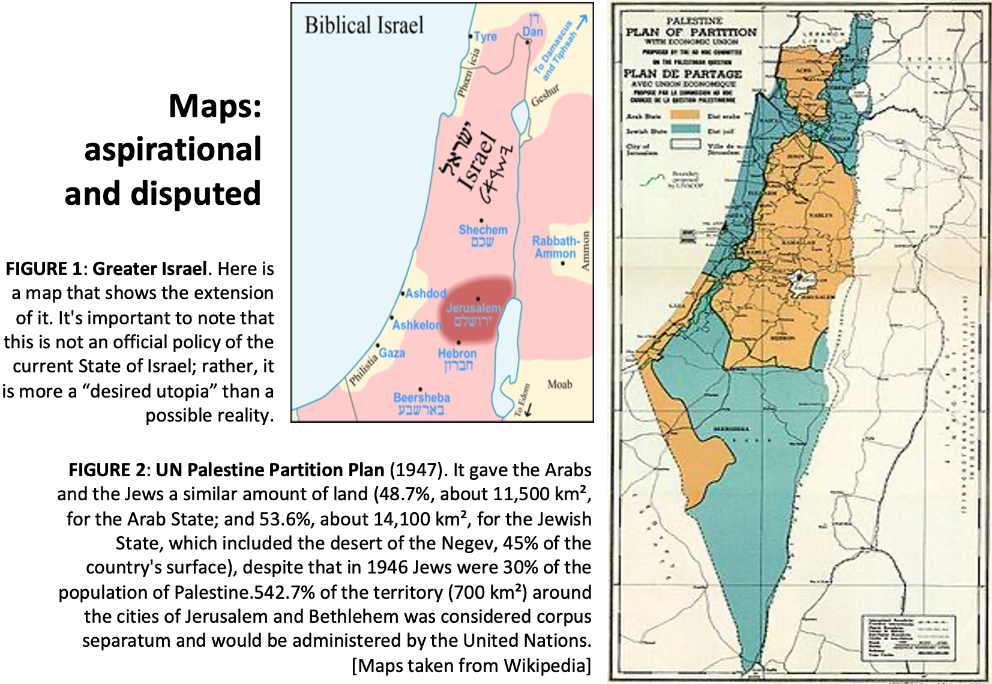

The current state of Israel, founded in 1948 with the partition of the British Protectorate of Palestine, argues its existence in the need for a Jewish state that not only represents and welcomes such a community but also meets its own religious requirements, since in Judaism the Hebrew is spoken as the “chosen people of God”, and Israel as its “Promised Land”. So, being the state of Israel the direct heir of the ancient Hebrew people, it would become the legitimate occupier of the lands quoted in Genesis 15: 18-21. This is known as the concept of Greater Israel (see map)[2].

On the Palestinian side, they exhibit as their main argument thirteen centuries of Muslim rule (638-1920) over the region of Palestine, from the Orthodox caliphate to the Ottoman Empire. They claim that the Jewish presence in the region is primarily based on the massive immigration of Jews during the late 19th and 20th centuries, following the popularization of Zionism, as well as on the expulsion of more than 700,000 Palestinians before, during and after the Arab-Israeli war of 1948, a fact known as the Nakba[3], and of many other Palestinians and Muslims in general since the beginning of the conflict. Some also base their historical claim on their origin as descendants of the Philistines.

However, although these arguments are weak, beyond historical conjecture, the reality is, nonetheless, that these aspirations have been the ones that have provoked the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. This properly begins in the early 20th century, with the rise of Zionism in response to the growing anti-Semitism in Europe, and the Arab refusal to see Jews settled in the area of Palestine. During the years of the British Mandate for Palestine (1920-1948) there were the first episodes of great violence between Jews and Palestinians. Small terrorist actions by the Arabs against Kibbutzim, which were contested by Zionist organizations, became the daily norm. This turned into a spiral of violence and assassinations, with brutal episodes such as the Buraq and Hebron revolts, which ended with some 200 Jews killed by Arabs, and some 120 Arabs killed by the British army.[4]

Another dark episode of this time was the complicit relations between the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Almin Al-Husseini, and the Nazi regime, united by a common agenda regarding Jews. He had meetings with Adolf Hitler and gave them mutual support, as the extracts of their conversations collect[5]. But it will not be until the adoption of the “United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine” through Resolution 181 (II) of the General Assembly when the war broke out on a large scale.[6] The Jews accepted the plan, but the Arab League announced that, if it became effective, they would not hesitate to invade the territory.

And so, it was. On May 14, 1948, hours after the proclamation of the state of Israel by Ben-Gurion, Israel was invaded by a joint force of Egyptian, Iraqi, Lebanese, Syrian and Jordanian troops. In this way, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War began, beginning a period of war that has not stopped until today, almost 72 years later. Despite the multiple peace agreements reached (with Egypt and Jordan), the dozens of United Nations resolutions, and the Oslo Accords, which established the roadmap for achieving a lasting peace between Israel and Palestine, conflicts continue, and they have seriously affected the development of the societies and peoples of the region.

The Israel Defense Forces

Despite the difficulties suffered since the day of its independence, Israel has managed to establish itself as the only effective democracy in the region, with a strong rule of law and a welfare state. It has a Human Development Index of 0.906, considered very high; is an example in education and development, being the third country in the world with more university graduates over the total population (20%) and is a world leader in R&D in technology. Meanwhile, the countries around it face serious difficulties, and in the case of Palestine, great misery. One of the keys to Israel's success and survival is, without a doubt, its Army. Without it, it would not have been able to lay the foundations of the country that it is today, as it would have been devastated by neighboring countries from the first day of its independence.

It is not daring to say that Israeli society is one of the most militarized in the world. It is even difficult to distinguish between Israel as a country or Israel as an army. There is no doubt that the structure of the country is based on the Army and on the concept of “one people”. The Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) act as the backbone of society and we find an overwhelming part of the country's top officials who have served as active soldiers. The paradigmatic example are the current leaders of the two main Knesset parties: Benny Ganz (former Chief of Staff of the IDF) and Benjamin Netanyahu (a veteran of the special forces in the 1970s, and combat wounded).

This influence exerted by the Tzahal[7] in the country is fundamentally due to three reasons. The first is the reality of war. Although, as we have previously commented, Israel is a prosperous country and practically equal to the rest of the western world, it lives in a reality of permanent conflict, both inside and outside its borders. When it is not carrying out large anti-terrorist operations such as Operation “Protective Edge,” carried out in Gaza in 2014, it is in an internal fight against attacks by lone wolves (especially bloody recent episodes of knife attacks on Israeli civilians and military) and against rocket and missile launches from the Gaza Strip. The Israeli population has become accustomed to the sound of missile alarms, and to seeing the “Iron Dome” anti-missile system in operation. It is common for all houses to have small air raid shelters, as well as in public buildings and schools. In them, students learn how to behave in the face of an attack and basic security measures. The vision of the Army on the street is something completely common, whether it be armored vehicles rolling through the streets, fighters flying over the sky, or platoons of soldiers getting on the public bus with their full equipment. At this point, we must not forget the suffering in which the Palestinian population constantly lives, as well as its harsh living conditions, motivated not only by the Israeli blockade, but also by living under the government of political parties such as Al-Fatah or Hamas. The reality of war is especially present in the territories under dispute with other countries: the Golan Heights in Syria and the so-called Palestinian Territories (the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip). Military operations and clashes with insurgents are practically daily in these areas.

This permanent tension and the reality of war not only affect the population indirectly, but also directly with compulsory military service. Israel is the developed country that spends the most defense budget according to its GDP and its population.[8] Today, Israel invests 4.3% of its GDP in defense (not counting investment in industry and military R&D).[9] In the early 1980s, it came to invest around 22%. Its army has 670,000 soldiers, of whom 170,000 are professionals, and 35.9% of its population (just over 3 million) are ready for combat. It is estimated that the country can carry out a general mobilization around 48-72 hours. Its military strength is based not only on its technological vanguard in terms of weapons systems such as the F-35 (and atomic arsenal), material, armored vehicles (like the Merkava MBT), but also on its compulsory military service system that keeps the majority of the population trained to defend its country. Israel has a unique military service in the western world, being compulsory for all those over 18 years of age, be they men or women. In the case of men, it lasts 32 months, while women remain under military discipline for 21 months, although those that are framed in combat units usually serve the same time as men. Military service has exceptions, such as Arabs who do not want to serve and ultra-Orthodox Jews. However, more and more Israeli Arabs serve in the armed forces, including in mixed units with Druze, Jews and Christians; the same goes for the ultra-orthodox, who are beginning to serve in units adapted to their religious needs. Citizens who complete military service remain in the reserve until they are 40 years old, although it is estimated that only a quarter of them do so actively.[10]

Social cohesion

Israeli military service and, by extension, the Israeli Defense Forces are, therefore, the greatest factor of social cohesion in the country, above even religion. This is the second reason why the army influences Israel. The experience of a country protection service carried out by all generations creates great social cohesion. In the Israeli mindset, serving in the military, protecting your family and ensuring the survival of the state is one of the greatest aspirations in life. From the school, within the academic curriculum itself, the idea of patriotism and service to the nation is integrated. And right now, despite huge contrasts between the Jewish majority and minorities, it is also a tool for social integration for Arabs, Druze and Christians. Despite racism and general mistrust towards Arabs, if you serve in the Armed Forces, the reality changes completely: you are respected, you integrate more easily into social life, and your opportunities for work and study after the enlistment period have increased considerably. Mixed units, such as Unit 585 where Bedouins and Christian Arabs serve,[11] allow these minorities to continue to throw down barriers in Israeli society, although on many occasions they find rejection from their own communities.

Israelis residing abroad are also called to service, after which many permanently settle in the country. This enhances the sense of community even for Jews still in the Diaspora.

In short, the IDF creates a sense of duty and belonging to the homeland, whatever the origin, as well as a strong link with the armed forces (which is hardly seen in other western countries) and acceptance of the sacrifices that must be made in order to ensure the survival of the country.

The third and last reason, the most important one, and the one that summarizes the role that the Army has in society and in the country, is the reality that, as said above, the survival of the country depends on the Army. This is how the military occupation of territories beyond the borders established in 1948, the bombings in civilian areas, the elimination of individual objectives are justified by the population and the Government. After 3,000 years, and since 1948 perhaps more than ever, the Israeli people depend on weapons to create a protection zone around them, and after the persecution throughout the centuries culminating in the Holocaust and its return to the “Promised Land,” neither the state nor the majority of the population are willing to yield in their security against countries or organizations that directly threaten the existence of Israel as a country. This is why despite the multiple truces and the will (political and real) to end the Arab-Israeli conflict, the country cannot afford to step back in terms of preparing its armed forces and lobbying.

Obviously, during the current Covid-19 pandemic, the Army is having a key role in the success of the country in fighting the virus. The current rate of vaccination (near 70 doses per 100 people) is boosted by the use of reserve medics from the Army, as well as the logistic experience and planning (among obviously many other factors). Also, they have provided thousands of contact tracers, and the construction of hundreds of vaccination posts, and dozens of quarantine facilities. Even could be arguable that the military training could play a role in coping with the harsh restrictions that were imposed in the country.

The State-Army-People trinity exemplifies the reality that Israel lives, where the Army has a fundamental (and difficult) role in society. It is difficult to foresee a change in reality in the near future, but without a doubt, the army will continue to have the leadership role that it has assumed, in different forms, for 3,000 years.

[1] Genesis 15:18 New International Version (NIV). 18: “On that day the Lord made a covenant with Abram and said, ‘To your descendants I give this land, from the Wadi [a] of Egypt to the great river, the Euphrates’.”

[2] Great Israel matches to previously mentioned Bible passage Gn. 15: 18-21.

[3] Independent, JS (2019, May 16). This is why Palestinians wave keys during the 'Day of Catastrophe'. Retrieved March 23, 2020, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/nakba-day-catastrophe-palestinians-israel-benjamin-netanyahu-gaza-west-bank-hamas-a8346156.html

[4] Ross Stewart (2004). Causes and Consequences of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. London: Evan Brothers, Ltd., 2004.

[5] Record of the Conversation Between the Führer and the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem on November 28, 1941, in in Berlin, Documents on German Foreign Policy, 1918-1945, Series D, Vol. XIII, London , 1964, p. 881ff, in Walter Lacquer and Barry Rubin, The Israel-Arab Reader, (NY: Facts on File, 1984), pp. 79-84. Retrieved from https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-mufti-and-the-f-uuml-hrer#2. “Germany stood for uncompromising war against the Jews. That naturally included active opposition to the Jewish national home in Palestine .... Germany would furnish positive and practical aid to the Arabs involved in the same struggle .... Germany's objective [is] ... solely the destruction of the Jewish element residing in the Arab sphere .... In that hour the Mufti would be the most authoritative spokesman for the Arab world. The Mufti thanked Hitler profusely. ”

[6] United Nations General Assembly A / RES / 181 (II) of 29 November 1947.

[7] Tzahal is a Hebrew acronym used to refer to the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF).

[8] Newsroom. (8th. June 2009). Arming Up: The world's biggest military spenders by population. 03-20-2020, by The Economist Retrieved from: https://www.economist.com/news/2009/06/08/arming-up

[9] Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. (nd). SIPRI Military Expenditure Database. Retrieved March 21, 2020, from https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex

[10] Gross, JA (2016, May 30). Just a quarter of all eligible reservists serve in the IDF. Retrieved March 22, 2020, from https://www.timesofisrael.com/just-a-quarter-of-all-eligible-reservists-serve-in-the-idf/

[11] AHRONHEIM, A. (2020, January 12). Arab Christians and Bedouins in the IDF: Meet the members of Unit 585. Retrieved March 19, 2020, from https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/The-sky-is-the-limit-in-the- IDFs-unique-Unit-585-613948

Preparan proyectar “poder de combate creíble” en la nueva era de “competición estratégica”

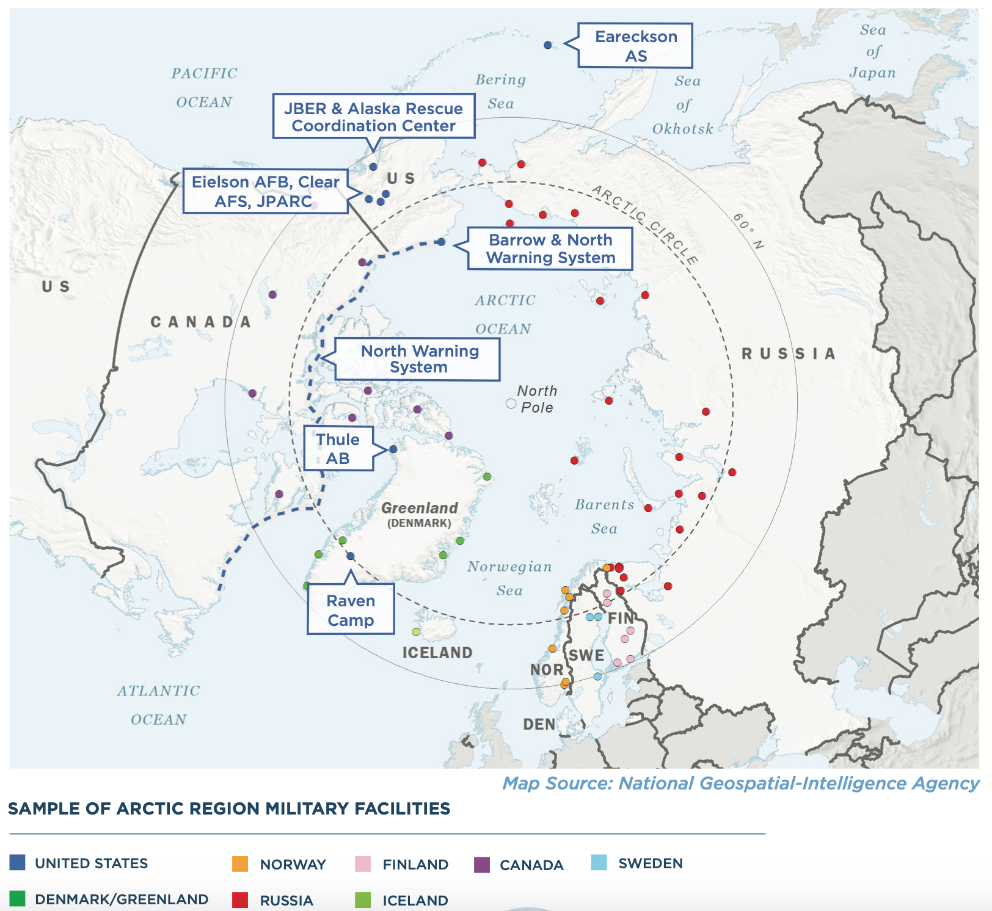

Si el Ártico fue un importante escenario en la Guerra Fría, en la nueva tensión geopolítica su progresivo deshielo incluso acentúa sus características estratégicas. El Departamento de Defensa de Estados Unidos adecuó en 2019 su estrategia para el Ártico a los nuevos planteamientos de rivalidad con Rusia y China, y luego su concreción ha correspondido a las fuerzas más involucradas en esa región: en 2020 la Fuerza Aérea presentó su propio documento y en este 2021 lo ha hecho la Armada, implicando también al Cuerpo de Marines y la Guardia Costera. Las directrices buscan garantizar la proyección de “poder de combate creíble”.

La tripulación del submarino USS Connecticut en los ejercicios ICEX 2020 [US Navy]

ARTÍCULO / Pablo Sanz

El Ártico es importante por la riqueza natural aún por explotar que contiene su subsuelo (el 22% de los depósitos de hidrocarburo del mundo, que por lo que afecta al petróleo serían 90.000 millones de barriles) y por su posición estratégica en el globo: ahí confluyen las dos grandes masas continentales de Eurasia y América. La apertura de nuevas rutas marítimas gracias al progresivo deshielo no solo supone una ventaja comercial, sino además capacita actuar militarmente con mayor rapidez sobre ese y sobre otros escenarios.

Son muchos los países interesados en promover la cooperación y multilateralismo en la región, y así se hace desde el Consejo Ártico; no obstante, el complejo entorno de seguridad del Círculo Polar Ártico ha llevado a las principales potencias a fijar estrategias para defender sus respectivos intereses. En el caso de Estados Unidos, el Departamento de Defensa actualizó en junio de 2019 la estrategia para el Ártico que había elaborado tres años antes, con el fin de adecuarla al nuevo planteamiento surgido con la Estrategia de Seguridad Nacional (NSS) de 2017 y trasladado a la Estrategia de Defensa Nacional (NDS) de 2018, documentos que dejan atrás la era del combate contra el terrorismo internacional y elevan a “rivalidad” la relación con China y Rusia, en una nueva situación geopolítica de “competición estratégica”.

La estrategia del Pentágono para el Ártico luego ha sido concretada por la Fuerza Aérea en un informe propio, presentado en julio de 2020, y después por la Armada, en enero de 2021. Con las mismas líneas generales, esos enfoques marco apuntan a tres objetivos:

1) Como “nación ártica”, por su soberanía sobre Alaska, Estados Unidos debe garantizar la seguridad en su territorio e impedir que desde posiciones polares pueda amenazarse otras partes del país.