In the image

Osama bin Laden and Ayman al Zawahiri during an interview with Pakistani journalist Hamid Mir, in November 2001 [H. Mir]

Ayman al Zawahiri, leader of Al Qaeda and direct successor of Osama bin Laden, was killed on July 30, 2022, at 6 am local time, via a drone strike conducted by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in Afghanistan’s capital city, Kabul. The US President Joe Biden confirmed two days later the death of the so-called ‘second emir’ and classified the operation as a “precision strike” that caused no civilian casualties. After 11 years at the forefront of the terrorist organization, Al Zawahiri’s reign of terror comes to an end.

Al Zawahiri came from a family of doctors; in fact, he worked in his native Egypt as an ophthalmologist. Alongside his medical career, since he was young, he was linked with various Islamist movements. He founded in 1979 the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, terrorist organization that assassinated former Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, main responsible of the Egypt-Israel peace treaty. Al Zawahiri was one of the arrested following the president’s assassination in October 1981.

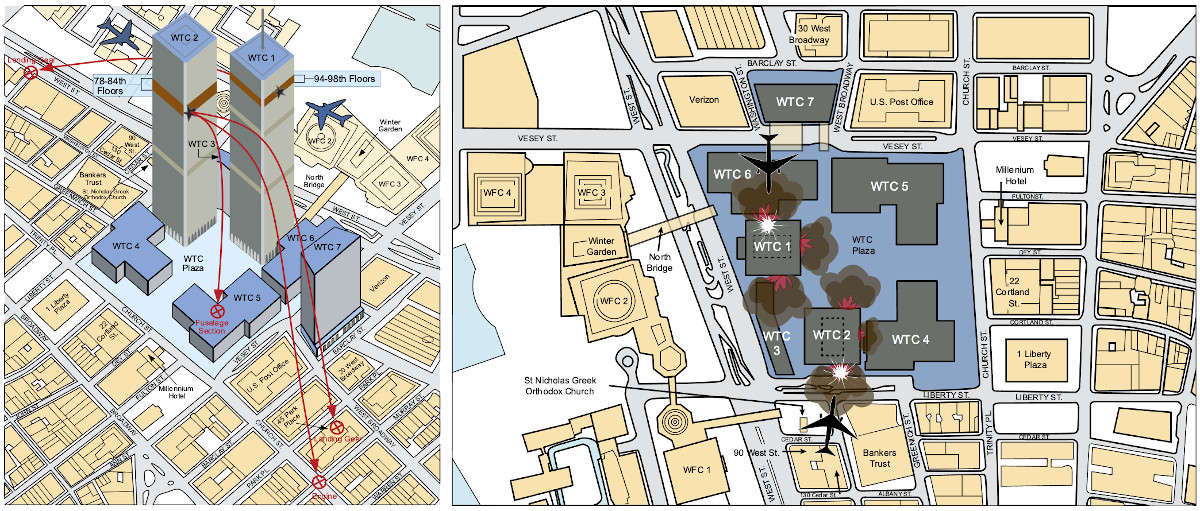

After three years in prison he escaped to Pakistan, where he joined the Afghan Jihad against the soviets. In Afghanistan, he met Osama bin Laden and Abdullah Azzam, with whom he co-founded Al Qaeda in 1998. Al Zawahiri became the main responsible of expanding and internationalizing the terrorist organization. The Taliban regime sheltered him in Afghanistan. It was during this time when he became the principal mastermind of some of the most notorious terrorist attacks performed by Al Qaeda, including the one against the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in September 2001.

After Bin Laden’s death, and thanks to the influence he racked up during his years at the forefront of the organization, he became the second emir of Al Qaeda. Nonetheless, Al Zawahiri was not as publicly known as Bin Laden once was. The Egyptian emir was not as charismatic as his Saudi predecessor.

With the rise of Daesh (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), Al Qaeda lost its influence, and Abu-Bakr al Baghdadi rose as the main jihadist figure of cult instead of Ayman al Zawahiri. The Egyptian emir lived a life of secrecy in Afghanistan, where the Taliban protected him until his death.

Having both succumbed to American military power, the assassination of Al Zawahiri was orchestrated and executed differently to that of his predecessor as head of Al Qaeda. Osama bin Laden was killed in Pakistan on May 2, 2011, at 1 am local time by Navy SEALs Team Six. The operation, codenamed ‘Neptune Spear’, was carried out by several coordinated military and intelligence groups of the US. It was primarily led by the CIA and the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) coordinating SEAL Team Six. Robert O’Neill was the SEAL that delivered the ‘coup de grace’ on the first emir.

Ayman al Zawahiri, on the other hand, was killed on July 30, 2022, at 6 am local time, via a drone strike. The operation was conducted by the CIA, and the ‘coup de grace’ was delivered from afar by a drone that dropped two AGM-144 Hellfire missiles targeting the exact position of Al Zawahiri and killing the second emir.

Compared to Operation ‘Neptune Spear’, the operation to kill Al Zawahiri was more surgically conducted; the family of Ayman did not suffer any casualties, whereas SEAL Team Six also killed four other individuals beyond the target: his adult son Khalid, a courier by the name of Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti, his brother Abrar, and Abrar’s wife, Bushra. Besides, no American life was directly put in harm’s way to execute the operation against Al Zawahiri. This shows the efficiency of the latter operation in comparison with the former. Moreover, it shows that the use of drones for the future counter-terrorist operations may be the way to go in order to avoid unwanted casualties.

Al Zawahiri’s legacy

Al Zawahiri’s legacy on Al Qaeda cannot be overlooked. As said previously, he wasn’t as charismatic as Bin Laden; in fact, Bruce Hoffman, director of the Georgetown University’s Center for Peace and Security Studies, described Zawahiri in 2011 as a leader with a “prickly and dogmatic” reputation. However, he also declared that, despite not having the Saudi’s “mellifluous voice”, Al Zawahiri had, however, “street credit”, and believed that the Egyptian emir would become an “even stronger leader than bin Laden.”

Actually, Hoffman’s prediction did not hold, mainly due to three reasons:

First, the Egyptian was a man of thought, not actions. Al Zawahiri is one of the five jihadist intellectuals that signed the 1998 fatwa “Jihad Against Jews and Crusades”, a statement/manifesto by the World Islamic Front which is considered by the 9/11 Commission Report in 2004 as the foundational document declaring the creation of Al Qaeda. In it, Bin Laden, Zawahiri, and three other scholars claimed that America had declared war against Allah. Moreover, in the manifesto, Al Zawahiri declared that “to kill Americans (…) is an individual duty for every Muslim.”

If we compare the most notorious attacks performed by Al Qaeda before and after Osama bin Laden’s killing in 2011, we observe that, under the leadership of the Saudi terrorist, the organization was much more active and fiercer than it was under the direction of Al Zawahiri. After 2001, the pressure exerted to Al Qaeda was immense. The US, alongside other western countries, initiated the ‘War on terror’, and the main objective of the Bush Administration was to eliminate the terrorist organization led by Osama bin Laden. The results of the pressure exerted by the West were visible and tangible. If we compare the most notable attacks by both emirs, we will observe how the acts of terrorism and casualties per attack decreased by a significant margin. Bin Laden’s most notorious attack was 9/11, in 2001, while the most remembered one by Al Zawahiri was the ‘Charlie Hedbo’ shooting, in 2015. The former killed around 3,000 civilians, the latter took a meager—though equally regrettable—toll of 12 casualties.

By 2020, the second emir had practically become a hermit. He became distant and his activity consisted of writing books and essays with little to none videos of himself delivering speeches. Al Zawahiri did not even commemorate the 20th anniversary of 9/11, neither did he address the fact that American troops withdrew from Afghanistan.