In the image

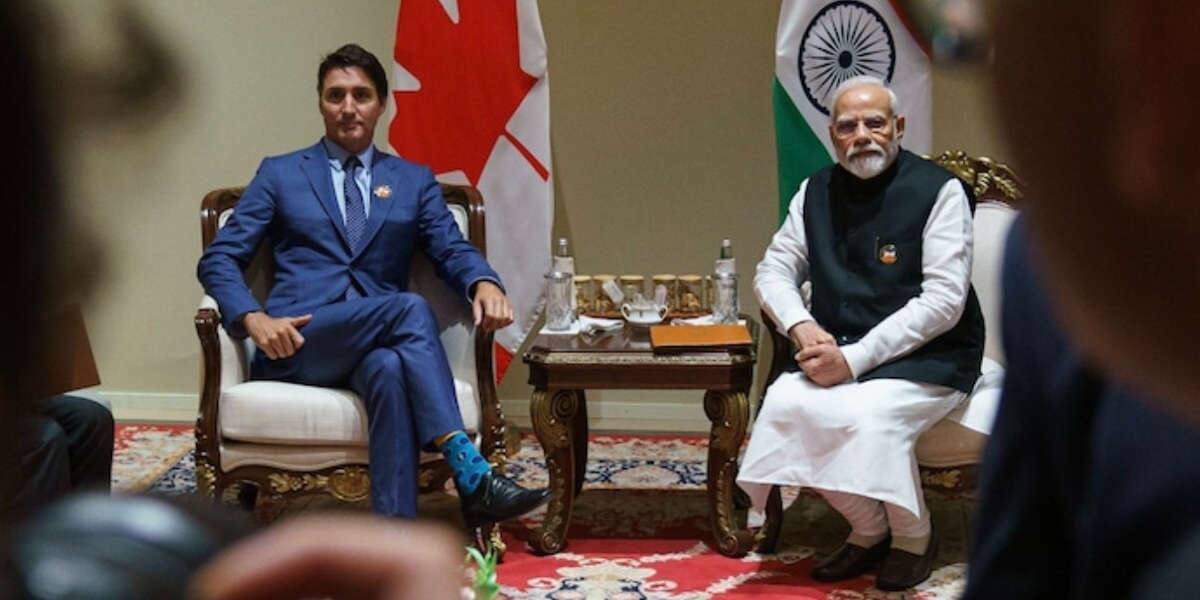

Prime Ministers Trudeau and Modi on the sidelines of the G20 Summit in India, September 2023 [ X/@JustinTrudeau]

Separated by thousands of kilometers, a mighty ocean, and half the Asian continent, the link between the Republic of India and Canada seems limited at first glance – if not completely nonexistent. Although the process and timing of British colonization manifested differently for the two nations, the 19th century saw both subjected to similar imperial policies, foreign administrators, and ‘middle-power’ dynamics. Under the careful eye of the crown, this profound link intensified at the beginning of the 20th century when a wave of an ethnoreligious group known as the Sikhs (‘community of the Khalsa’) migrated from mainly modern-day Punjab in Northern India to British Columbia. The Sikhs are followers of Sikhism, an Indian religion that originated at the end of the 15th century from the spiritual teachings of Guru Nanak (1469–1539). Scholars suggest that this initial wave of Sikh immigration was spurred by two British Commonwealth army regiment trips from India to Canada, for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897 and King Edward VII’s coronation in 1902, considering that many of the Sikhs came from military backgrounds.

Since then, Canada has become home to the largest Sikh population outside India. In the most recent census, about 770,000 people in Canada reported Sikhism as their religion. This number translates to around 2.1% of the country’s total population, serving as the source of the continuing human connection between the two states.

A sore point of relations: The Khalistan movement

The fragilities of this seemingly strong link have recently come to light with the diplomatic clashes surrounding the controversial Khalistan Movement. Launched around the 1940s independence of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan, the goal of the campaign is to set up a separate state for Sikhs in Punjab known as Khalistan (meaning the ‘Land of the Khalsa‘ or ‘Pure’). While originally similar to other secessionist movements, the method of achieving their goals has since become distinct and unconventional.

Recalling their military background, the late 20th century saw a reformed struggle characterized by violent ethnonationalism. The shift is attributed to Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale’s rise to Sikh leadership in 1982. Branded by the Indian state as a trained Indian militant, he was accused of fostering a climate of violencewherein his extremist followers committed mass killings, assassinations of opposition leaders, and bombings of civilian infrastructures in the name of responding to perceived injustices and political marginalization.

Given this nature of violence and frequent intervention in Indian affairs, the movement was violently suppressed by the Indian state and met with a controversial countermovement by Indian society. Their effortsincluded everything from all-out military operations (such as the infamous Operation Blue Star) to anti-Sikh communal riots. This weakened the movement considerably and brought it to an end in India in the 20th century.

Internationally, however, displaced followers of the violent Khalistan Movement began a trajectory toward societies where significant Sikh communities had already been established. The most significant import was to Canada, where they were accused of the 1985 terrorist attack on Air India Flight 182, small-scale armed operations, and bombings. Following the increase in associated violence, the Canadian government even designated two Khalistan Movement-associated groups as terrorist entities in 2003. These included the Babbar Khalsa International (BKI) and the International Sikh Youth Federation (ISYF).

This shift was perfectly summarized in a quote by Sikh advocate Jathedar of Akal Takht Giani Harpreet Singh, who noted that “...such incidents had made the Sikh community stronger and Sikhs would continue their struggle to get justice and would never be scared to stand with the truth.” While the Indian government could crush the movement’s body, it could not tear down its spirit.

From the shadows to the center stage: The India-Canada diplomatic dispute

While India and Canada shared deep political, economic, and social relations, the threat of the Khalistan Movement thus always seemed to loom in the diplomatic background. Over the years, these hidden hostilities have translated into frosty exchanges.

In February 2018, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau came under fire for the Canadian High Commissioner’s decision to invite Jaspal Singh Atwal, a former ISYF terrorist group member, to a state dinner in New Delhi. In December 2020, another spat occurred when India’s Ministry of External Affairs accused him of interfering in its internal affairs after he made “unwarranted” comments on Indian farmer protests allegedly “infiltrated by Khalistanis.” Likewise, September 2022 saw India expressing its “concern and disappointment” over Ottawa’s apparent inaction in the face of an unofficial voting exercise among Canadian Sikhs called the “Khalistan Referendum.”

Together, these seemingly small and insignificant exchanges paved the way for the outbreak of an all-out diplomatic crisis. It culminated in June 2023 with the shooting of Sikh leader Hardeep Singh Nijjar outside a temple in Vancouver.

A Sikh migrant to the province of British Columbia, Nijjar was known in Canada as a vocal advocate for “Sikhs' right to self-determination and independence of Indian occupied Punjab” and was believed to have been actively planning a non-binding Khalistani referendum at the time of his death. Contrastingly, he had been designated a “terrorist” by the Indian government since 2020. They cite his supposed involvement in a 2007 cinema bombing in Punjab, the 2009 assassination of Sikh Indian politician Rulda Singh, and the overall activities behind the banned militant group Khalistan Tiger Force (KTF).

In response to the controversial killing, anti-Indian sentiment and activities began to brew in Canada. More specifically, posters were distributed calling for violence against Indians, cash rewards were offered for the home addresses of Indian diplomats, and temples were vandalized.

Amidst these growing tensions, Canada unexpectedly paused trade negotiations with India on 1 September. They did not state an explicit reason for doing so, but an anonymous official mentioned that the pause was “to take stock of where [the two countries] are.” More than a week later, the tensions became even clearer at the G20 summit held in New Delhi, wherein Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi held bilateral meetings with many world leaders – except Trudeau.

Instead, the bulk of their exchanges occurred on the sidelines and were described as frosty. Modi conveyed his concerns about the Sikh community protests in Canada, and Trudeau voiced discomfort at India’s worsening human rights record while also insinuating issues of foreign interference. Days after the tense G20 summit, a spokesperson for Canadian Trade Minister Mary Ng announced the postponement of a trade mission to India previously scheduled for October.

Things took a turn for the worse on 18 September 2023. Exactly two months after the shooting of Nijjar, Trudeau spoke before Parliament, informing them that Canada’s security agencies would begin investigating “credible allegations of a potential link” between Indian government agents and the violent events. He stressed that since Nijjar gained citizenship in 2007, the acts would be interpreted as an unacceptable violation of its sovereignty by a foreign government. He ended the address by calling on the Indian government to cooperate in the investigation.

A day later, Canada expelled an Indian diplomat. India retaliated by doing the same, citing “growing concern at the interference of Canadian diplomats in…internal matters and their involvement in anti-India activities.” As tensions escalated over the following month, Canada recalled 41 diplomats after the Indian government claimed that it would revoke its diplomatic immunity. In doing so, the Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister pointed out that India’s threat could be considered contrary to international law (particularly the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations). The Asian state called the allegations “absurd” and “motivated,” reiterating that it remains a “democratic polity with a strong commitment to [the] rule of law.” In turn, it urged Canada to take legal action against “anti-Indian” elements operating from its soil, claiming that the “unsubstantiated allegations seek to shift the focus from Khalistani terrorists and extremists, who have been provided shelter in Canada and continue to threaten India’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.”

Almost a year would pass by before the next great development in the crisis.

On 3 May 2024, three Indian nationals (Kamalpreet Singh, Karanpreet Singh, and Karan Brar) were arrested by Canadian enforcement and charged with first-degree murder and conspiracy to commit murder for Nijjar’s death. More than a week later, a fourth suspect (Amandeep Singh) was charged on the same grounds. Despite the arrests, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) stressed that the investigation remained open as they were “aware that others may have played a role in this homicide, and…remain dedicated to finding and arresting each one of these individuals.”

In doing so, the RCMP claimed that it was able to gather “ample, clear and concrete evidence” that established linkages between six Indian government agents and activities that “threaten public safety in Canada.” Such included “clandestine information-gathering techniques, coercive behavior targeting South Asian Canadians, and involvement in over a dozen threatening and violent acts, including murder.” In turn, India was asked to cooperate with further investigations by waiving diplomatic and consular immunities for such individuals. When they refused to do so, Canada served notices of expulsion to six Indian diplomats. Less than a week later, India ordered the same of Canada’s Acting High Commissioner and five other diplomats.

The bilateral consequences of conflict

This chain of events has been a point of concern due to its economic, social, and political consequences at a bilateral level.

First, the conflict is predicted to have insignificant immediate effects from a financial standpoint, but its long-term consequences remain ambiguous. Officially, India and Canada have expressed their desires to prevent the diplomatic fallout from immediately impacting bilateral trade. Despite the pause in trade negotiations, both states have published statements reassuring their full commitment to engaging with and supporting their “well-established commercial ties,” currently valued at around $8 billion. Still, scholars caution that further economic growth could be hindered if the situation becomes more hostile through the imposition of tariffs or other forms of economic retaliation. A former Canadian diplomat summarizes this challenge in one word: uncertainty. The problem, he warns, is that the changing nature of the situation might incentivize businesses and individuals to look for more stable opportunities elsewhere. In such a case, both states face the risk of suffering significant financial losses.

Next, both countries pride themselves on the profound “people-to-people” connections that they share through their large migrant communities. However, this reality necessitates a considerable and effective diplomatic staff to ensure that their needs are met. Unfortunately, the tit-for-tat expulsions have caused a reduction in government agents carrying out diplomatic work. For potential Indian migrants, immigration lawyers have expressed concern that this tension could negatively affect their plans to work, study, or visit family in Canada. While immigration processing remains operational, they warn that applicants may expect delays in issuing visas, filing paperwork, and fulfilling other administrative tasks. Simultaneously, the conflict leaves the active diaspora communities equally vulnerable. As anti-immigration and xenophobic sentiments rise, fewer resources and services may be afforded for the protection of civilians abroad. From a social perspective, the conflict thus seems to disproportionately affect individuals over other key actors.

Finally, the tensions may have territorially expanded a phenomenon known as “vote bank politics” that was historically considered exclusive to South Asian statecraft. In his 1950s essay entitled "The Social Structure of a Mysore Village," M. N. Srinivas coined the term based on an observation that the pluralistic nature of Indian society may have caused differing (and sometimes even clashing) political interests among castes, communities, or religious groups. Recognizing that favorable electoral outcomes and the aggregation of power would only be possible through widespread popular support, early forms of Indian political parties thus mobilized voters based on their social identities by promising them various forms of material and non-material benefits. Politicians would then act as patrons by providing the pledged resources, favors, and representation to those client communities. He called such groups “vote banks” as he believed their collective voting behavior could be predictably swayed in favor of a particular party or candidate. Based on the values of obligation and reciprocity, the phenomenon thus reflects a potential transactional nature of Indian politics.

Nowadays, it is said this concept remains highly relevant yet genetically different in contemporary Indian statecraft. While underlying political dynamics remain largely unchanged, time may have seen shifts in the composition of specific vote bank groups as well as the physical location of the phenomenon. On this note, India and the Canadian opposition party have accused the Trudeau Government of adopting the political practice in a strategic attempt to secure the Sikh vote. One of his former foreign policy advisers, Omer Aziz, even argues that the timing of the crackdowns on Canada’s South Asian ally was no coincidence. While slight tensions have always been present between the two countries, he points out that Trudeau’s emboldened public support for Sikhs began with his February 2018 visit to India – a mere 4 months after the election of a new leader of the opposition New Democratic Party (NDP): Jagmeet Singh.

A devout, turban-wearing, and kirpan-carrying Sikh, the rise of Singh as the first person of color to lead a federal party in the country’s history was hailed as “a historic milestone” for Sikh-Canadians by the World Sikh Organization of Canada. In a feat unseen by political rivals, Singh was able to offer a direct line to the ethnoreligious minority group, becoming a champion of their rights and freedoms at a national level. Furthermore, his party also seemed popular amongst a network of sovereignist and sympathetic individuals called Le Réseau Cap sur l'Indépendance (RCI) in the province of Quebec. Like the Sikhs, the region is also surrounded by controversy as the battleground of a movement advocating for a separate, sovereign state for its French-speaking populace. Despite hostility to the central government, the NDP unexpectedly surged to victory among Quebec residents in what was dubbed an “Orange Wave” during the 2011 elections. Overall, the ability of Singh and his party to appeal to traditionally politically apathetic voting groups seemingly threatened the incumbent’s hold over power. Perhaps left with no other choice, distorting Canada’s long-term foreign policy priorities may have been seen as the only issue that would overcome Canada’s domestic ethnic battles.

A battle of norms: Security vs sovereignty

It would be foolish to work under the assumption that the diplomatic crisis has unfolded in a vacuum wherein only India, Canada, and their constituents are at stake.

At an international level, the hostilities also seem to have consequences on the ongoing normative debate amongst scholars of International Relations. On the one hand, India argues that the defense of its national security is its main interest in the conflict. It sees the violent Khalistan Movement and Canada’s supposed sheltering of it as a legitimate threat to its territorial integrity that must be actively squashed through diplomatic tools. On the other hand, Canada’s interest lies in protecting its sovereignty. As the highest authority in the land, the state sees India’s actions towards the diaspora community living on its territory as a direct interference in its domestic affairs. More than that, it also regards it as a violation of the internationally recognized Principle of Non-Intervention.

Overall, both may be considered legitimate interests stemming from equally legitimate concerns. What then takes precedence?

The question is difficult to answer. If India’s security is prioritized over Canada’s sovereignty or vice versa, it may set a dangerous precedent in the world community. It sends the message that one’s internal politics can serve as a possible justification for blatant violations of international standards. If other actors internalize and imitate this lack of commitment to upholding multilateral obligations as much as national ones, the stability of the entire rules-based international system is put at risk.

It is also worth noting that this current crisis and its surrounding circumstances may change with Trudeau’s January 2025 resignation announcement. In his place, former central banker Mark Carney rose as the leader of the ruling Liberal Party and as the new Canadian Prime Minister on 9 March 2025. This act may not only end Trudeau’s nine-year stretch as the Prime Minister of the North American country, but it may even bring a shift to the policy handling of the diplomatic crisis. In contrast, India’s Modi has had a strong hold on the South Asian nation for more than a decade. Since 2014, he has allegedly advanced Hindu nationalism to unprecedented levels at the expense of making brazen attacks against minorities (particularly Muslims and Sikhs). Thus, critics fear that India’s democracy may be faltering as civil institutions face growing threats and the line between religion and state becomes blurrier under his rule.

Given these two extremes, crucial questions about the future of Canada-India relations arise. While Trudeau’s government held a confrontational stance toward India, the newly-elected Carney faces two options as he takes over during a possibly tumultuous time in Canada: continue this antagonizing approach or adopt a more conciliatory policy. If the first stance is adopted, alignment with Trudeau’s policies may lead to persistent tensions and the further escalation of diplomatic disputes. If the second is prioritized, a change in tone in the areas of trade and diplomatic engagement could not only repair relations but even mark the beginning of a new phase in bilateral ties of a cooperative nature rather than a conflictual one – at the expense of long-standing security concerns.

To this end, India and Canada must find new yet responsible ways to address their domestic ethnic battles. This sustainable and inclusive solution can only be achieved in the spirit of cooperation, respect for equally legitimate normative interests, and the transcendence of the politics of the government of the day. The reason is simple. More than a security issue or a sovereignty matter, this diplomatic gridlock raises a humanitarian crisis due to the vulnerable Sikh thread that pulls these two seemingly different states together.