Efforts by France, NATO and the UK

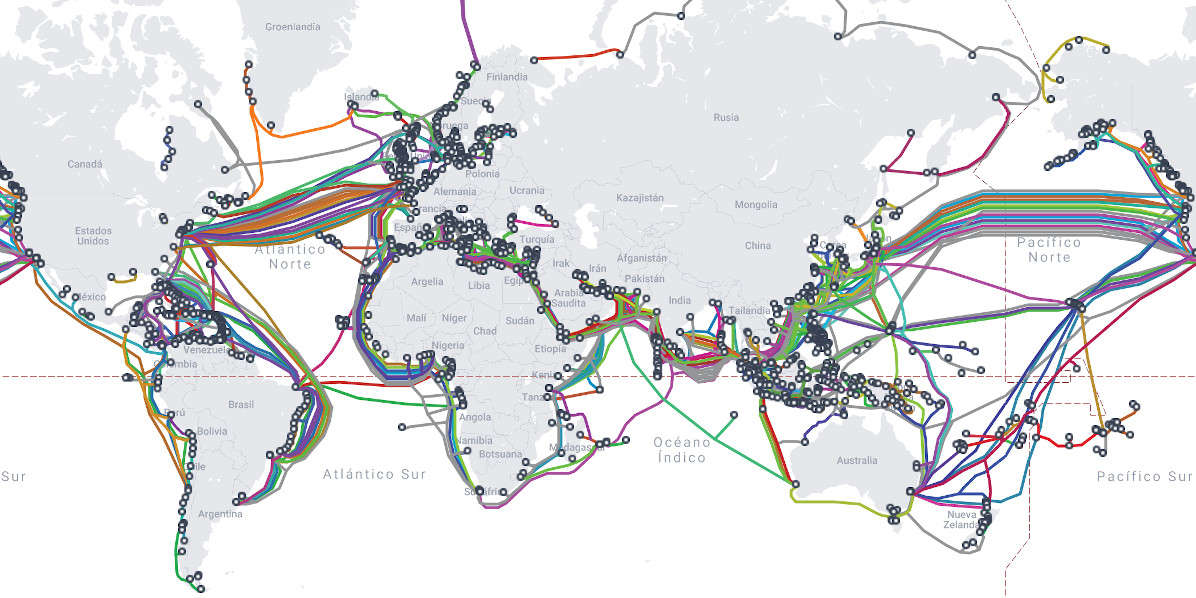

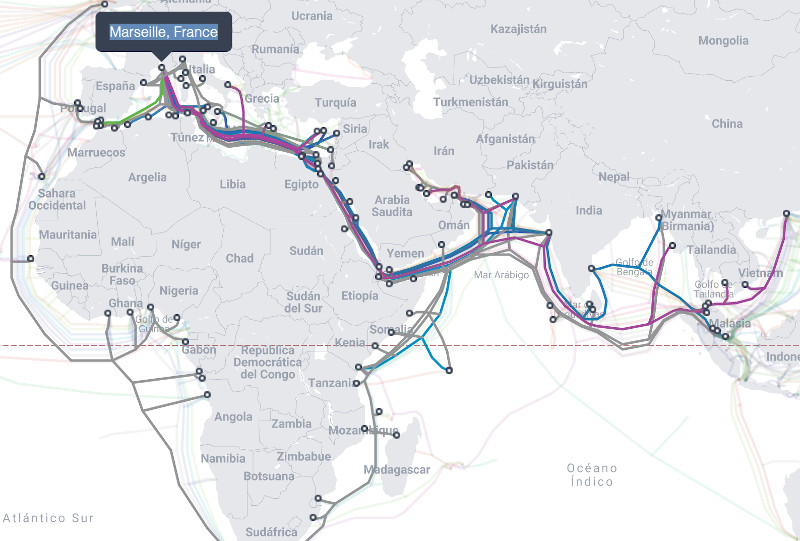

In this context of exposure of undersea cables, prior to the incident, France had already boosted their surveillance around its undersea infrastructures prior to the incident, as announced in mid-October, when.President Emmanuel Macron publicly unveiled the purchase of a deep-sea drone and a robot to be used against these kinds of attacks. The initiative is part of a military program of the French government expected to be deployed by 2025, with the robots able to reach depths of 6,000 meters. Yet, having such a fleet of drones to boost surveillance doesn’t ensure sufficient protection, especially for a country like France, given the vast number of cables it has extended along the seabed, specially for a country like France. With around 30 cables coming into its territory, and the wide range of techniques available to damage these infrastructures, the task is of considerable difficulty. Cyrille Dalmont, a researcher at the Institut Thomas Moore Institute, suggests a plausible way to make sabotages harder is to increase the number of operational cables. According to him, the only real defense would be “to lay down further cable lines”, so that a concrete act of sabotage “can´t result in a blackout.”

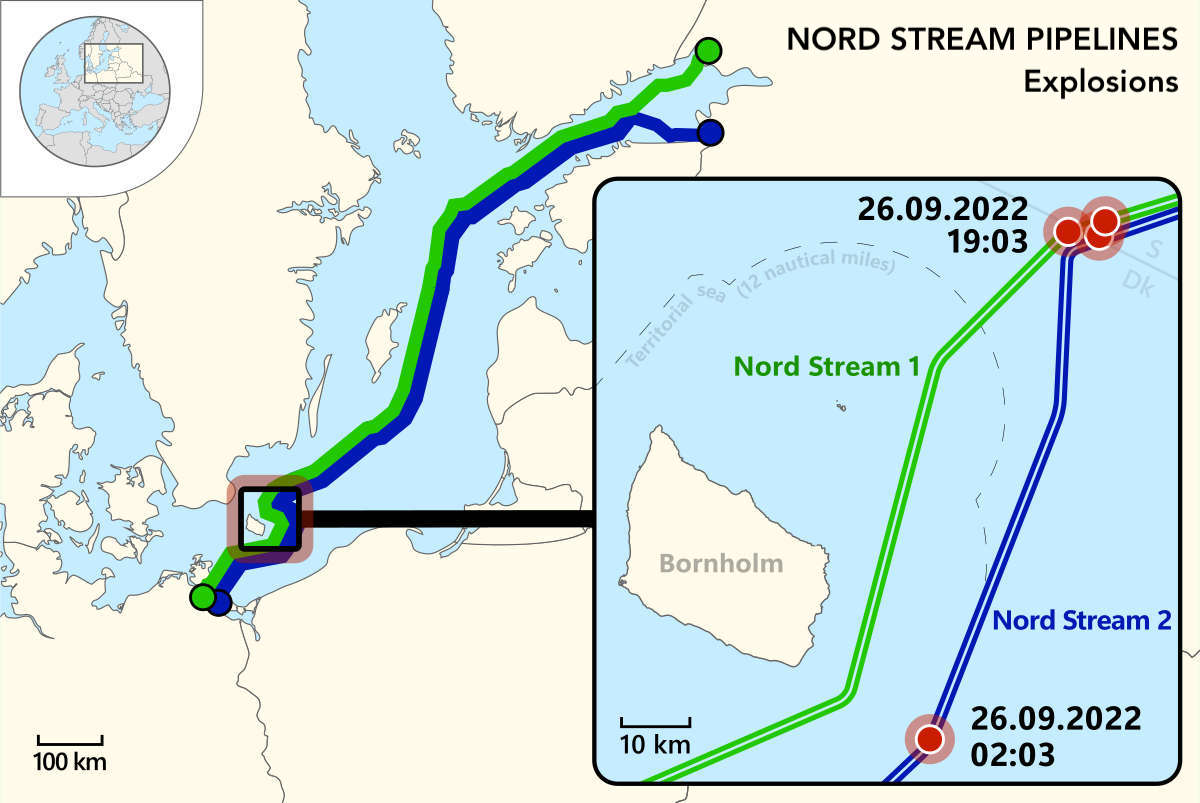

In early 2023, NATO defense ministers announced a plan to strengthen undersea infrastructure and prevent incidents like the one happening with the Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines. Their explosion, confirmed as a sabotage with explosives, is yet another example of critical undersea infrastructure that remains vulnerable to hostile intentions at the same time as being easily to disrupt. Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg announced the establishment of a Critical Undersea Infrastructure Coordination Cell at NATO. Led by German Lieutenant General Hans-Werner Wiermann, this center represents a positive initiative and starting point for the Alliance to keep building on; the face of the challenge Russia or China could pose if restoring to the disruption of allied undersea critical infrastructure. So, how is it that these critical infrastructures can be protected? There are several nations across the Mediterranean region and other parts of the world which rely on a certain number of these cables to carry out their daily operations, and for which an incident disrupting the traffic these lines carry with them would have terrible consequences. Thus, it is in their best interest to ensure their undersea infrastructure can be adequately monitored and preserved from external attacks. France is among those nations.

Protecting their its extensive network of undersea critical infrastructure is among the top priorities for the French government. Having the second largest maritime area in the world, France is particularly concerned about the fact that only two of its robots are able to dive below 2,000 meters. This leaves many cables in a vulnerable position against hybrid attacks. Currently, development and maintenance of these infrastructures is in the hands of private companies such as Japan’s NEC, France’s Alcatel Submarine Networks, or US’ SubCom.

According to Colin Wall, from the CSIS, “given the multi-faceted nature of the use, private ownership, and vulnerabilities of subsea cables, international action would necessarily need to leverage different formats to be effective.” He recommends six particular strategies that could be applied in order to increase security, from which it is worth mentioning the development of national monitoring and repair capabilities. An initiative like this would push for each nation with vulnerable infrastructure to upgrade their its capabilities, monitoring and surveillance measures. Some examples of nations who have already applied this are the United Kingdom or France. The former announced back in March 2021 the development of a new Multi Role Ocean Surveillance Ship especially designed to patrol waters near critical underwater infrastructures. Through the use of sensors and autonomous drones, the vessel is expected to be part of the British Armed Forces’ modernizationprogram. As UK´s Defensce Secretary Ben Wallace argued back then, “some of our new investments will therefore go into ensuring that we have the right equipment to close down these newer vulnerabilities.”

Other measures Wall proposes include increasing intelligence sharing among allied nations, promoting national risk assessments of the different cable projects, making sure private companies comply with all required measures that guarantee the highest standards of these cables’ security, or even bringing to the table the possibility of adopting a complete international legal framework that includes undersea cables (the current legal framework embodied by UNCLOS does not provide full protection to undersea infrastructure). As he points out, these are just ideas which could help many nations to become aware of the importance of such infrastructures, and be the base line for further discussions on how to secure them.

As previously mentioned, France , on its side, is investing in new capabilities and vehicles which can dive deeper than current unmanned drones. Included as part of their its new military program to fight against hybrid threats, their effective incorporation will allow for enhanced surveillance capabilities while ensuring wider freedom of action around their undersea cables. The French Government also unveiled its Seabed Warfare Strategy earlier in 2022. This document, which establishes the France’s desire to extend their its underwater capabilities down to 6,000 meters through the use of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUV) and Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROV). These initiatives will add to the existing programs already being implemented by the French Navy. The Capacité Hydrographique et Océanographique Futur (CHOF) is in charge of providing New Generation Hydrographic Vessels; and the Système de Lute Anti-Mines will be developed to replace the traditional mine-warfare capabilities used until now for new autonomous and unmannedinhabited ones.

Sensors are a potentially beneficial instrument to monitor the situation of undersea cables. According toDimitrios Eleftherakis and Raul Vicen-Bueno Eleftherakis and Vicen-Bueno, from the NATO Center for Maritime Research and Experimentation, there are four different types of sensors: acoustic, magnetic, optical and oceanographic. Acoustic sensors are an efficient instrument to monitor the seabed given their wider ranges of detection. This way, when incorporated aboard surface vessels, they can monitor the water column immediately below. Magnetic sensors can be useful to detect nayany significant ferreous object, such as an anchor. On the opposite, oOptical sensors are useful for closer revisions at a concrete spot in shallow waters, given their relative shorter range of no more than 20 meters.

Steps by Taiwan, Norway and the US

On the opposite side of the globe, Taiwan is also taking significant steps to secure theirits undersea cables and ensure a quick response to any attack given the threat posed by China. Most recently, Taipei announced an incorporation of communication breakdowns into the war drills they usually carry out, to improve Taiwan’s response capabilities and ensure fast reaction times to any malicious attack. Among other solutions which are beingunder consideredation, the use of high-speed satellites to boost connectivity, like Starlink’s Elon Musk’s Starlink did in Ukraine after Russian attacks, has attracted the attention of many.

And just like Taiwan, many other regions in the world like the Arctic are experiencing sabotages across their undersea infrastructures. The High North, a region bound to see rising numbers of undersea cables over the following years, also saw damage to infrastructure in the area ofundersea cables from Svalbard ibeing damaged in early 2022. These and many other instances prove how critical undersea infrastructure will remain an essential element in the field of maritime security, and thus, nations vulnerable to these kinds of incidents, like France, will have to tighten their surveillance and security measures around them.

A particular example of current initiatives implemented to strengthen cable protection, and from which other governments may be able to learn, is the US´Cable Ship Security Program (CSSP). Through it, the US government pays an annual stipend to a number of vessels under its flag to remain available full-time and provide a fast response in case any undersea infrastructure directly affecting the US is damaged. This way, they ensure any attack or incident can be quickly reached and repaired. As of 2022, the US has the Cable Security Fleet operating along its coasts, which recently reflagged an additional vessel in February 2022 to be incorporated to service.

The need of serious protection

The threats posed by undersea cables’ weak protection are widespread, and are bound to influence the security policies of many across the entire globe during the following years. The EU has gotten more serious in this aspect over the past years to prevent these incidents from happening. According to Camille Morel, researcher at the Lyon Institute for Strategy and Defense Studies, “the political attention paid specifically to marine cables is ultimately quite recent. It dates back to the 2010s. The EU is starting to intervene concretely, even if it remains timid, by financing alternative cables.”

France is considered to be one of the major bridgeheads of in Europe for transatlantic undersea cables. French authorities and affected companies carried out an investigation of its their underwater infrastructure after the incident with the Nord S Sstream took place; while also reinforcing surveillance on them. However, the recent events have demonstrated theseir efforts are not enough, and thus, they must keep investing in new strategies to strengthen their undersea infrastructures’ protection.

In order to ensure better protection of undersea critical infrastructures, there is a wide variety of instruments and resources to be used. Sensors are among them, with the extensive range of types and uses they have. Yet, such uses also imply a significant investment on them prior to that; and as Dimitrios Eleftherakis and Raul Vicen-Bueno Eleftherakis and Vicen-Bueno underline in their work, “it is not possible to monitor the environment of the cables with only one type of sensor and platform. A network of them is needed.”

Thus, governments need to get serious about the protection of undersea cable and pipelines , and invest accordingly in order to acquire equipment to monitor their own infrastructures. At the end of the day, it is up to each nation to invest efforts to prevent these incidents, for which further patrols and surveillance exercises are required. It also implies labeling the protection of national undersea critical infrastructures among the top national security priorities.