ESSAY / Elena López-Dóriga

The European Union’s aim is to promote democracy, unity, integration and cooperation between its members. However, in the last years it is not only dealing with economic crises in many countries, but also with a humanitarian one, due to the exponential number of migrants who run away from war or poverty situations.

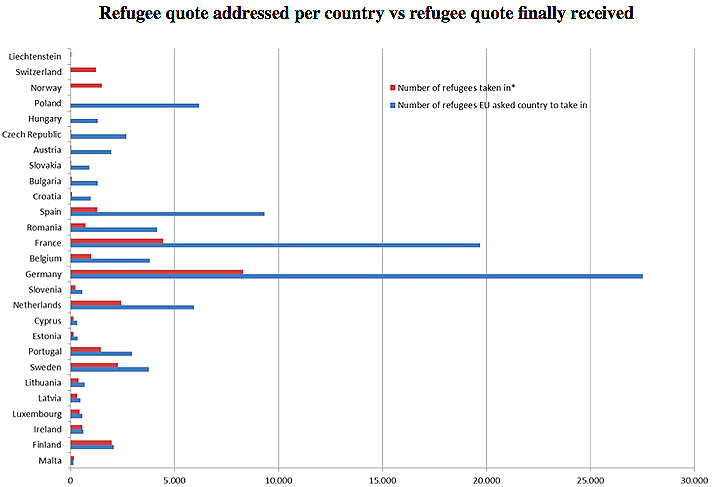

When referring to the humanitarian crises the EU had to go through (and still has to) it is about the refugee migration coming mainly from Syria. Since 2011, the civil war in Syria killed more than 470,000 people, mostly civilians. Millions of people were displaced, and nearly five million Syrians fled, creating the biggest refugee crisis since the World War II. When the European Union leaders accorded in assembly to establish quotas to distribute the refugees that had arrived in Europe, many responses were manifested in respect. On the one hand, some Central and Eastern countries rejected the proposal, putting in evidence the philosophy of agreement and cooperation of the EU claiming the quotas were not fair. Dissatisfaction was also felt in Western Europe too with the United Kingdom’s shock Brexit vote from the EU and Austria’s near election of a far right-wing leader attributed in part to the convulsions that the migrant crisis stirred. On the other hand, several countries promised they were going to accept a certain number of refugees and turned out taking even less than half of what they promised. In this note it is going to be exposed the issue that occurred and the current situation, due to what happened threatened many aspects that revive tensions in the European Union nowadays.

The response of the EU leaders to the crisis

The greatest burden of receiving Syria’s refugees fell on Syria’s neighbors: Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. In 2015 the number of refugees raised up and their destination changed to Europe. The refugee camps in the neighbour countries were full, the conditions were not good at all and the conflict was not coming to an end as the refugees expected. Therefore, refugees decided to emigrate to countries such as Germany, Austria or Norway looking for a better life. It was not until refugees appeared in the streets of Europe that European leaders realised that they could no longer ignore the problem. Furthermore, flows of migrants and asylum seekers were used by terrorist organisations such as ISIS to infiltrate terrorists to European countries. Facing this humanitarian crisis, European Union ministers approved a plan on September 2015 to share the burden of relocating up to 120,000 people from the so called “Frontline States” of Greece, Italy and Hungary to elsewhere within the EU. The plan assigned each member state quotas: a number of people to receive based on its economic strength, population and unemployment. Nevertheless, the quotas were rejected by a group of Central European countries also known as the Visegrad Group, that share many interests and try to reach common agreements.

Why the Visegrad Group rejected the quotas

The Visegrad Group (also known as the Visegrad Four or simply V4) reflects the efforts of the countries of the Central European region to work together in many fields of common interest within the all-European integration. The Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia have shared cultural background, intellectual values and common roots in diverse religious traditions, which they wish to preserve and strengthen. After the disintegration of the Eastern Block, all the V4 countries aspired to become members of the European Union. They perceived their integration in the EU as another step forward in the process of overcoming artificial dividing lines in Europe through mutual support. Although they negotiated their accession separately, they all reached this aim in 2004 (1st May) when they became members of the EU.

The tensions between the Visegrad Group and the EU started in 2015, when the EU approved the quotas of relocation of the refugees only after the dissenting votes of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia were overruled. In asking the court to annul the deal, Hungary and Slovakia argued at the Court of Justice that there were procedural mistakes, and that quotas were not a suitable response to the crisis. Besides, the politic leaders said the problem was not their making, and the policy exposed them to a risk of Islamist terrorism that represented a threat to their homogenous societies. Their case was supported by Polish right-wing government of the party Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice) which came to power in 2015 and claimed that the quotes were not comprehensive.

Regarding Poland’s rejection to the quotas, it should be taken into account that is a country of 38 million people and already home to an exponential number of Ukrainian immigrants. Most of them decided to emigrate after military conflict erupted in eastern Ukraine in 2014, when the currency value of the Ukrainian hryvnia plummeted and prices rose. This could be a reason why after having received all these immigration from Ukraine, the Polish government believed that they were not ready to take any more refugees, and in that case from a different culture. They also claimed that the relocation methods would only attract more waves of immigration to Europe.

The Slovak and Hungarian representatives at the EU court stressed that they found the Council of the EU’s decision rather political, as it was not achieved unanimously, but only by a qualified majority. The Slovak delegation labelled this decision “inadequate and inefficient”. Both the Slovak and Hungarian delegations pointed to the fact that the target the EU followed by asserting national quotas failed to address the core of the refugee crisis and could have been achieved in a different way, for example by better protecting the EU’s external border or with a more efficient return policy in case of migrants who fail to meet the criteria for being granted asylum.

The Czech prime minister at that time, Bohuslav Sobotka, claimed the commission was “blindly insisting on pushing ahead with dysfunctional quotas which decreased citizens’ trust in EU abilities and pushed back working and conceptual solutions to the migration crisis”.

Moreover, there are other reasons that run deeper about why ‘new Europe’ (these recently integrated countries in the EU) resisted the quotas which should be taken into consideration. On the one hand, their just recovered sovereignty makes them especially resistant to delegating power. On the other, their years behind the iron curtain left them outside the cultural shifts taking place elsewhere in Europe, and with a legacy of social conservatism. Furthermore, one can observe a rise in skeptical attitudes towards immigration, as public opinion polls have shown.

|

* As of September 2017. Own work based on this article

|

The temporary solution: The Turkey Deal

The accomplishment of the quotas was to be expired in 2017, but because of those countries that rejected the quotas and the slow process of introducing the refugees in those countries that had accepted them, the EU reached a new and polemic solution, known as the Turkey Deal.

Turkey is a country that has had the aspiration of becoming a European Union member since many years, mainly to improve their democracy and to have better connections and relations with Western Europe. The EU needed a quick solution to the refugee crisis to limit the mass influx of irregular migrants entering in, so knowing that Turkey is Syria’s neighbor country (where most refugees came from) and somehow could take even more refugees, the EU and Turkey made a deal the 18th of March 2016. Following the signing of the EU-Turkey deal: those arriving in the Greek Islands would be returned to Turkey, and for each Syrian sent back from Greece to Turkey one Syrian could be sent from a Turkish camp to the EU. In exchange, the EU paid 3 billion euros to Turkey for the maintenance of the refugees, eased the EU visa restrictions for Turkish citizens and payed great lip-service to the idea of Turkey becoming a member state.

The Turkey Deal is another issue that should be analysed separately, since it has not been defended by many organisations which have labelled the deal as shameless. Instead, the current relationship between both sides, the UE and V4 is going to be analysed, as well as possible new solutions.

Current relationship between the UE and V4

In terms of actual relations, on the one hand critics of the Central European countries’ stance over refugees claim that they are willing to accept the economic benefits of the EU, including access to the single market, but have shown a disregard for the humanitarian and political responsibilities. On the other hand, the Visegrad Four complains that Western European countries treat them like second-class members, meddling in domestic issues by Brussels and attempting to impose EU-wide solutions against their will, as typified by migrant quotas. One Visegrad minister told the Financial Times, “We don’t like it when the policy is defined elsewhere and then we are told to implement it.” From their point of view, Europe has lost its global role and has become a regional player. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban said “the EU is unable to protect its own citizens, to protect its external borders and to keep the community together, as Britain has just left”.

Mr Avramopolus, who is Greece’s European commissioner, claimed that if no action was taken by them, the Commission would not hesitate to make use of its powers under the treaties and to open infringement procedures.

At this time, no official sanctions have been imposed to these countries yet. Despite of the threats from the EU for not taking them, Mariusz Blaszczak, Poland´s former Interior minister, claimed that accepting migrants would have certainly been worse for the country for security reasons than facing EU action. Moreover, the new Poland’s Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki proposes to implement programs of aid addressed to Lebanese and Jordanian entities on site, in view of the fact that Lebanon and Jordan had admitted a huge number of Syrian refugees, and to undertake further initiatives aimed at helping the refugees affected by war hostilities.

To sum up, facing this refugee crisis a fracture in the European Union between Western and Eastern members has showed up. Since the European Union has been expanding its boarders from west to east integrating new countries as member states, it should also take into account that this new member countries have had a different past (in the case of the Eastern countries, they were under the iron curtain) and nowadays, despite of the wish to collaborate all together, the different ideologies and the different priorities of each country make it difficult when it comes to reach an agreement. Therefore, while old Europe expects new Europe to accept its responsibilities, along with the financial and security benefits of the EU, this is going to take time. As a matter of fact, it is understandable that the EU Commission wants to sanction the countries that rejected the quotas, but the majority of the countries that did accept to relocate the refugees in the end have not even accepted half of what they promised, and apparently they find themselves under no threats of sanction. Moreover, the latest news coming from Austria since December 2017 claim that the country has bluntly told the EU that it does not want to accept any more refugees, arguing that it has already taken in enough. Therefore, it joins the Visegrad Four countries to refuse the entrance of more refugees.

In conclusion, the future of Europe and a solution to this problem is not known yet, but what is clear is that there is a breach between the Western and Central-Eastern countries of the EU, so an efficient and fair solution which is implemented in common agreement will expect a long time to come yet.

Bibliography:

J. Juncker. (2015). A call for Collective Courage. 2018, de European Commission Sitio web.

EC. (2018). Asylum statistics. 2018, de European Commission Sitio web.

International Visegrad Fund. (2006). Official Statements and communiqués. 2018, de Visegrad Group Sitio web.

Jacopo Barigazzi (2017). Brussels takes on Visegrad Group over refugees. 2018, de POLITICO Sitio web.

Zuzana Stevulova (2017). “Visegrad Four” and refugees. 2018, de Confrontations Europe (European Think Tank) Sitio web.

Nicole Gnesotto. (2015). Refugees are an internal manifestation of an unresolved external crisis. 2018, de Confrontations Europe (European Think Tank) Sitio web.