En la imagen

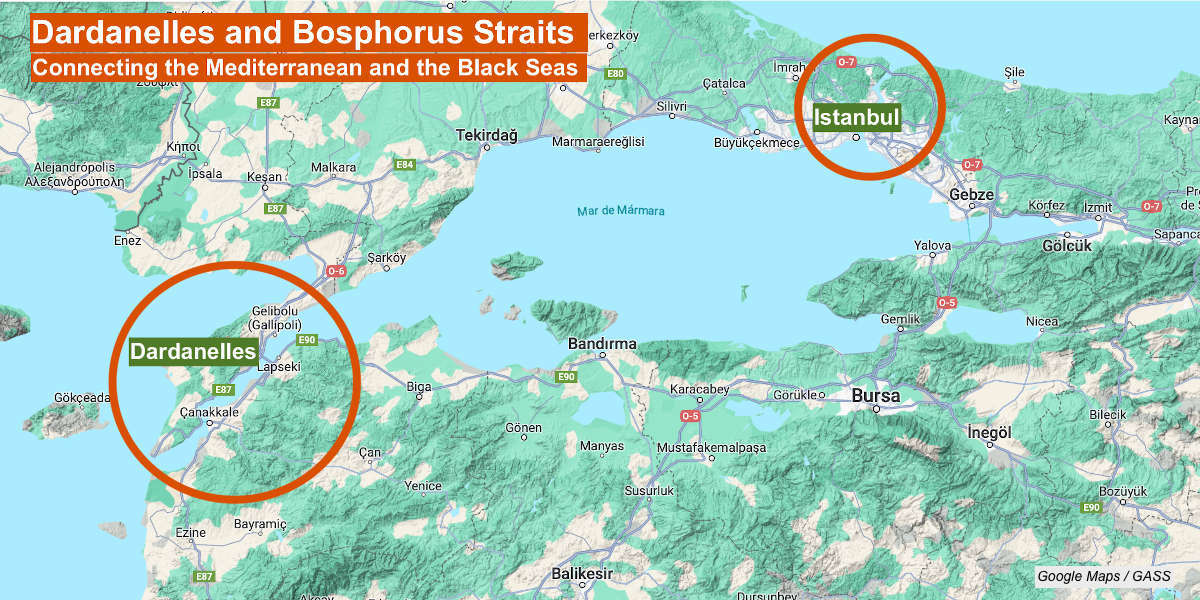

Dardanelles and Bosphorus Straits, in Turkey [Google Maps / GASS]

Following the suspension of the Black Sea Grain Deal back in July, commerce across the Black Sea region (upon which millions of people depend for their food supplies) has faced numerous challenges due to the large amounts of sea mines laid around its waters and littorals. NATO has decided to stand up a naval task force, made up of vessels from Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey, which will face several challenges with the massive amounts of mines spread across the region.

Since the suspension of the Black Sea Grain Deal in July, an ongoing debate has been opened on whether NATO should deploy one of its Standing Maritime Groups (SNMGs) to the region as a means to assist commerce bound for- and out of Ukrainian ports of Odessa and Chornomorsk. Without any agreement on the issue, largely due to the problematic situation that the Montreux Convention creates with its regime over the Turkish Straits, NATO has finally decided to stand up a naval task force, independent from the other SNMGs and exclusively made up of Bulgarian, Romanian and Turkish vessels (the three NATO countries with coasts in the Black Sea). It will not be a NATO operation such as the ongoing Operation Sea Guardian in the Mediterranean, but rather a naval force to complement the existing SNMGs.

To better understand the meaning and importance of such decision, several key issues must be addressed.

NATO's Standing Maritime Groups

Since the 1960s, NATO has had permanent naval forces deployed across the different maritime areas of strategic interests (mostly, the Baltic, the North Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and the Black Sea). The idea, a brainchild of U.S. Navy Admiral Richard Colbert to strengthen naval cooperation between Washington and the U.S. Navy, resulted in the establishment of three different maritime groups: Standing Naval Force Atlantic (STANAVFORLANT), Standing Naval Force Mediterranean (STANAVFORMED), and Standing Naval Force Channel (STANAVFORMEDCHAN).

These groups were composed of vessels from American and European navies, with a variable number of warships ranging from five to nine in each of them, deployed by the Member nations on a rotational basis. They were in charge of ensuring the Alliance had a permanent naval presence in all strategically-relevant seas, performing a wide variety of tasks and conducting joint exercises together to boost their interoperability.

Since the 1960s, these groups have been in constant evolution in terms of purpose, mission and operational areas, and as of today, NATO has four different groups. Standing NATO Maritime Groups 1 and 2, and Standing NATO Mine Countermeasures Groups 1 and 2. The latter two, as their name suggests, are exclusively focused on conducting tasks related to mine warfare and mine countermeasures, while the other two are made up of frigates and destroyers which perform a wider range of tasks and missions.

Although not the most popular at this precise moment, the standing maritime groups have traditionally been one of NATO's most important assets, especially when having to deter a powerful enemy as the Soviet Navy during the days of the Cold War. Since the end of it, however, their tasks were reoriented to fulfill other missions in a less contested and more cooperative maritime environment that lasted until Russia´s invasion of Crimea in 2014.

Now that great power competition has returned to the international arena, NATO faces a more contested and polarized maritime environment, with an increasing number of threats to its security. Perhaps, the time has come to rethink the current structure of its maritime groups so that it can better handle

The Montreux Convention and the problem with the straits

The Montreux Convention was signed in 1936, granting Turkey the administrative control over both the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles straits. Since then, Turkey has held control of the region, carefully guarding the only gate to the Black Sea region. With the outbreak of the conflict in Ukraine in February 2022, Turkey invoked article 19 of the convention and announced the closing of the straits to Russian and Ukrainian warships. The cited article establishes that during times of war and without a direct involvement of Turkey in it, all warships enjoy freedom of transit through them except for those of any party involved in the conflict.

This meant that Russia was no longer able to send additional warships into the region to support its land forces from the littoral. The Russian Navy, as the Soviet Navy before, has always faced major problems due to the lack of naval bases and ports with access to the world oceans. The Baltic Fleet based in Kaliningrad has to transit through the Danish Straits, effectively preventing it to launch any surprise incursion into the Atlantic. Likewise, the Northern Fleet has to transit through the GIUK Gap in the North Atlantic, and the Black Sea Fleet through the Turkish Straits to make it into the Mediterranean.

But just as Russia, NATO has also had some difficulties due to the Montreux Convention. Right after the news about the end of the grain deal were made public, an important debate started on whether NATO should send warships from one of its SNMGs to ensure the safe transit of commerce in the region. This option presented several challenges for the Alliance, especially with Turkey's reluctance to make an exception to the notification requirements established in the convention in order to allow NATO warships through. Additionally, the vast amounts of naval mines which we will discuss below was also a major complication.

Thus, the example of this situation could open the debate on whether the structure and distribution of the SNMGs should be modified to assign a group to each of the maritime regions, to be constitute by the navies in that region. However that may be, it seems clear that the need to establish a maritime force to clear the region while the SNMGs cannot contribute is indicative of a need for change.

The nature of the challenge moving forward

Immediately after the suspension of the Black Sea Grain Deal, Russia threatened to attack any vessel coming out or to Ukrainian ports and launched several attacks to the port of Odessa to prove its resolution on the matter. This decision has had similar effects to that of a naval blockade imposed in times of war, and has prevented commercial shipping to flow across the region as it did under the agreement.

As explained in a previous piece back in July, the current state of the Black Sea waters with thousands of naval mines requires strong mine sweeping capabilities in order to support the transit of commercial vessels without danger of hitting a mine. Initial responses to this disruption weighted establishing an alternative maritime corridor closer to the coast of NATO countries Romania and Bulgaria, so that Russia would not interfere. The idea derived from the Tanker War during the 1980s, when the United States began flagging tankers so that they would not be targeted by Iranian forces which were trying to disrupt oil exports from the Gulf region.

Yet, although the initiative was not finally adopted in its entirety, naval mines still are a major threat to shipping—as the incident on October 5 involving a Turkish tanker showcased. Clearing naval mines is an arduous task that takes time, and is highly demanding for the forces assigned to do so. Knowing that NATO naval forces are still clearing mines from the Second World War in the Baltic Sea may help to understand the magnitude of the challenge.

The decision taken by Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey will likely yield positive results for commerce in the region, while also allowing smaller navies in the Alliance to undertake a significant task, but they will undoubtedly face several challenges with the massive amounts of mines spread across the region. The establishment of this group in itself is a solid evidence of the challenges that NATO's naval forces will face in this new era of strategic during what has been called “the maritime century.”