En la imagen

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and Chinese President Xi Jinping meet for the first time at a private bilateral gathering during the 2022 APEC summit in Bangkok, Thailand [Philippine Presidency]

For decades, a conflict in the South China Sea has ‘defined’ Southeast Asia—fueled by competing sovereignty claims by bordering states like Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam, China, and the Philippines.

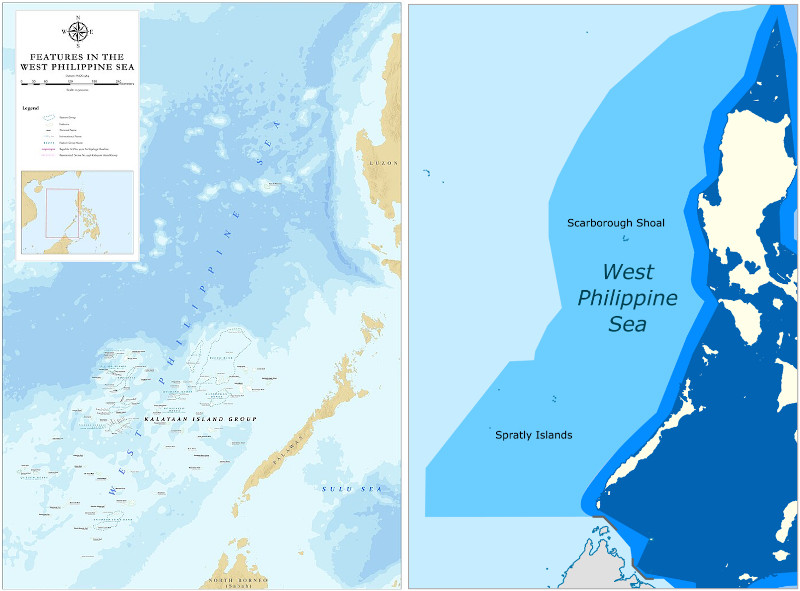

Between the latter two, a relatively dormant political disagreement persisted before a tense standoff in the Scarborough Shoal disrupted the status quo in 2012. Consequently, both states have implemented distinct strategies to respond to the bitter conflict. On the one hand, China has religiously pursued a 9-dash line policybased on a map introduced in 1947 that illustrates a U-shaped boundary encompassing about 90% of the contested waters. In contrast, the hedging approach of the Philippines can be likened to a fluctuating pendulum swinging between aggressive lawfare and superpower appeasement.

Many theorize that the latter’s complex foreign policy has been influenced by an equally complicated blend of factors. A report by the Defense Technical Information Center specifically identifies 1) a colonial legacy inspiring a general pattern of a US-Philippine alliance, 2) a perceived threat from China’s military capabilities as a global superpower, 3) the recognition and subsequent prioritization of economic gains from bilateral trade with China, and 4) the role of ASEAN as a third-party arbiter conducting diplomatic consultations. Nonetheless, these factors solely focus on the ‘external’ influences on the Philippine foreign strategy, as is the norm with the dominant neorealist international relations theory.

As a result, there seems to be a research gap in analyzing the country as more than a mere pawn in a political game between global superpowers. This current essay thus aims to examine ‘national-level’ factors of the issue—based on the argument of Filipino researchers that domestic dynamics may “influence [Philippine] foreign policy and its outcomes” from the inside out. An internal analysis of constitutional provisions and normative factors will be conducted because they reflect both objective and subjective realities in Philippine politics. Together, these factors could holistically explain why a response to the West Philippine Sea dispute (as it is known locally) has rarely survived longer than the term of the President of the time, and more interestingly, how each succeeding leader pursues a completely paradoxical strategy that reverses previous efforts. Without discrediting dominant theories on foreign behavior, they could shed light on the country’s inability to institutionalize a strategy at the political-regional level despite the stability of their territorial claim in the legal sphere.

Constitutional factors: Reviewing the rules of the game

Beginning at a national level, intentionally fabricated provisions in the Philippine political system seem conducive to how the country’s foreign policy develops. At the heart of this idea lies the 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines, which serves as the official codification of policies and practices that define the conduct of the nation’s statecraft.

Under Article II Section 1, the Philippines explicitly establishes itself as a “democratic” and “republican” state. Such a system bestows power to the Filipino People to elect representatives (specifically a president) to conduct politics on their behalf. Nonetheless, it may also be more likely for a Head of State to act on a ‘perceived’ legitimacy. Based on a flawed rationale that they received a direct mandate through election by a popular majority vote, leaders may justify creating a foreign policy as they see fit.

Nonetheless, the political system is not exclusive to the Philippines. Amongst other stakeholders in the South China Sea issue, the United States of America also adheres to a presidential model. Unlike the former, however, their foreign policy approach has been cohesive and long-term, bringing up the question of what ‘exactly’ makes the Philippines so different if they share the same structural DNA.

The answer lies in the proximity of the countries to the issue. As established, the Philippines has sovereignty claims over the region. They are at the heart of the maritime conflict and have more at stake than the US, which has the safety net of the Pacific Ocean separating it from the legal and physical battle. Thus, the Philippines’ interests may be more nuanced. This complexity allows state leaders to see multiple facets of the conflict (for example, both economic benefits but also military threats) and subsequently create a policy based on that perspective. In contrast, the US’ pivot to Asia can be attributed to only one goal: to contain a “Chinese power surge that is threatening [their] position in global affairs.” Thus, their balancing act remains the same regardless of which US President is in office.

To this end, it can also be seen that the system in itself may not be to blame but also how it is implemented in a country. In the Philippines, the extensive powers the presidential model bestows the Head of Government allows the state response towards the maritime dispute to be heavily dependent on their personal goals or area of expertise. This institutional factor could explain why as a professional economist, former President Arroyo’s foreign policy focused on the ‘commercial incentives’ of a joint oil-exploration deal in the disputed waters, or why as a military general, former President Ramos’ strategy focused on an ‘aggressive national defense’ and the strengthening of the country’s forces in the region. If the US had as big of a stake in the issue, its stance could be as dynamic as that of the Philippines. In reality, however, the collective interest of the state grounds the policy of the Head of Government in a way that incentivizes them not to exploit the system.

When further comparing the presidential model to the more popular parliamentary system, it is also seen that it cultivates an environment wherein parties (as well as the accountability measures and the ideological coherence they bring) are less significant to the elected official’s political plan. Because presidents rely on general population support to get elected while prime ministers rely on support from their peers, weaker party identification and higher electoral volatility in a presidential system may constitute favorable terrain for the personalization of politics. Historically, this premise seems true in the Philippines as nearly half of its former presidents switched parties, formed new ones, or left the party system altogether to run independently. In the strategy towards the maritime dispute, they may effectively act arbitrarily without an anchor to a state interest.

When compared again to the US which adopts the ‘same’ model but has a coherent policy, its system seems not as similar to the Philippines as one may initially think. While the Asian state follows the norm among adoptees of this model of keeping parties insignificant, the US hosts a “two-party system [that is] an outlier in the modern world.” Thus, its interpretation of the presidential system may seem closer than traditional to the parliamentary model since the election of the chief executive relies on peer support as much as the aforementioned general population support. In what many call “primary politics,” candidates from the Democratic and Republican parties are first internally nominated by their peers before running on their party’s behalf in general US elections. This double requirement makes it so that the elected US president is more accountable to other government officials than their Philippine counterparts. In terms of foreign policy, the chief executive may be less likely to change their stance on the dispute because they have a stronger ideological anchor.

That is not to say that arbitration of foreign policy is accepted in the Philippines. A legal safeguard known as the Philippine Foreign Service Act of 1991 was implemented to combat the creation of a strategy heavily dependent on the interests of one individual. This mandate explicitly requires the national government to adopt an objective foreign policy based on three pillars: 1) the preservation and enhancement of national security, 2) the promotion and attainment of economic security, and 3) the protection of the rights and promotion of the welfare and interest of Filipinos overseas. Still, many argue that subjective domestic variables such as leadership style, decision-makers’ mentalities, and a bureaucratic political model may affect the direction of Philippine foreign policy more than the aforementioned pillars. As a result, the simultaneous existence of an objective framework and behavioral factors may reveal a misalignment within the Philippine political system that could further translate into a weakness at the international level. While this reality means that the Philippines’ foreign policy is flexible when a president feels necessary, it also implies that instability and drastic change could occur when that leader leaves office.

This is where the Constitution’s rules regarding terms and reelections come in to reinforce this ambiguous reality. Article VII Section 4 states that citizens elect the president and vice-president for a limited term of 6 years, with the former’s ineligibility for personal reelection. In a nation formerly plagued by long-term dictatorship, arbitrary martial law, and impeachments, the goal is to ensure the occurrence of elections at regular intervals and to redirect the focus of an incumbent from mere re-election to effective governance. However, further analysis reveals an unintended consequence that simultaneously prevents policy ‘continuity’in the Philippine strategic culture. With just 6 years in office, it has been next to impossible for a clear and long-standing strategic policy to stick. This phenomenon is worsened by the existence of a trend wherein one’s political opponent succeeds the presidency and overturns the policy that took 6 years to enforce.

The best example of this idea is the shift in foreign policy during the presidential succession between Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, Benigno Aquino III, and Rodrigo Duterte. It started with Arroyo’s government fully embracing “the opportunity to become China’s strong partner” in the fields of trade, oil exploration, and overall economic reform. Nonetheless, her self-proclaimed “golden age of friendship between the Philippines and China” was cut short when her successor took office. From 2010 to 2016, Aquino took what is arguably the ‘most aggressive’ response to the maritime conflict in Philippine history. His strategy was characterized by frequent diplomatic protests, lawfare at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, and even systematic changes in the way the conflict is discussed locally by formally changing the name of the disputed area to the “West Philippine Sea.” It was during this time that the small-archipelagic State seemed to truly challenge China’s regional hegemony. Following the previous trend, however, this progress seemingly reversed when Duterte entered office. Regressing to a foreign policy that cultivated warmer relations with Beijing, he opened up the country to Chinese trade and investment while simultaneously making an enemy of one of the Philippines’ longest allies: the US. His foreign policy was characterized by a strategic leveraging of one global superpower against another.

Altogether, these provisions enshrined in the Constitution seem to both result in and support a continued reality of a foreign strategy defined by unsteady domestic politics.